Through a quiet, meditative expression, a Chilean arhitect of Croatian origin, pushes forward the Chilean myth to the global architectural scene.

A myth, because the identitarian image of that South American country is reflected by his performances, exhibitions, and installations, complementing his personal artistic talent. Thus the very purpose of architecture is fulfilled, however in the case of Radić’s practical work, through a distinct note of subtlety in his rendition, especially when taking into account the current state of global architecture, where identity, heritage and designing within given contexts are often accepted superficially or in such manner where faux or confusing elements are in use.

Smiljan, whose ancestors fled Dalmatia, seems to have conveyed the “Mediterranean myth” having it firmly grounded in the soil of his homeland, whose shores are washed away by the Pacific. The appearance of his practical work in that context symbolizes a breakthrough of the subtlest European thinking about architecture and visual arts in general, deliberately confronted, yet never conflicted to the distinct image of Chile.

Copper House 2, 2005

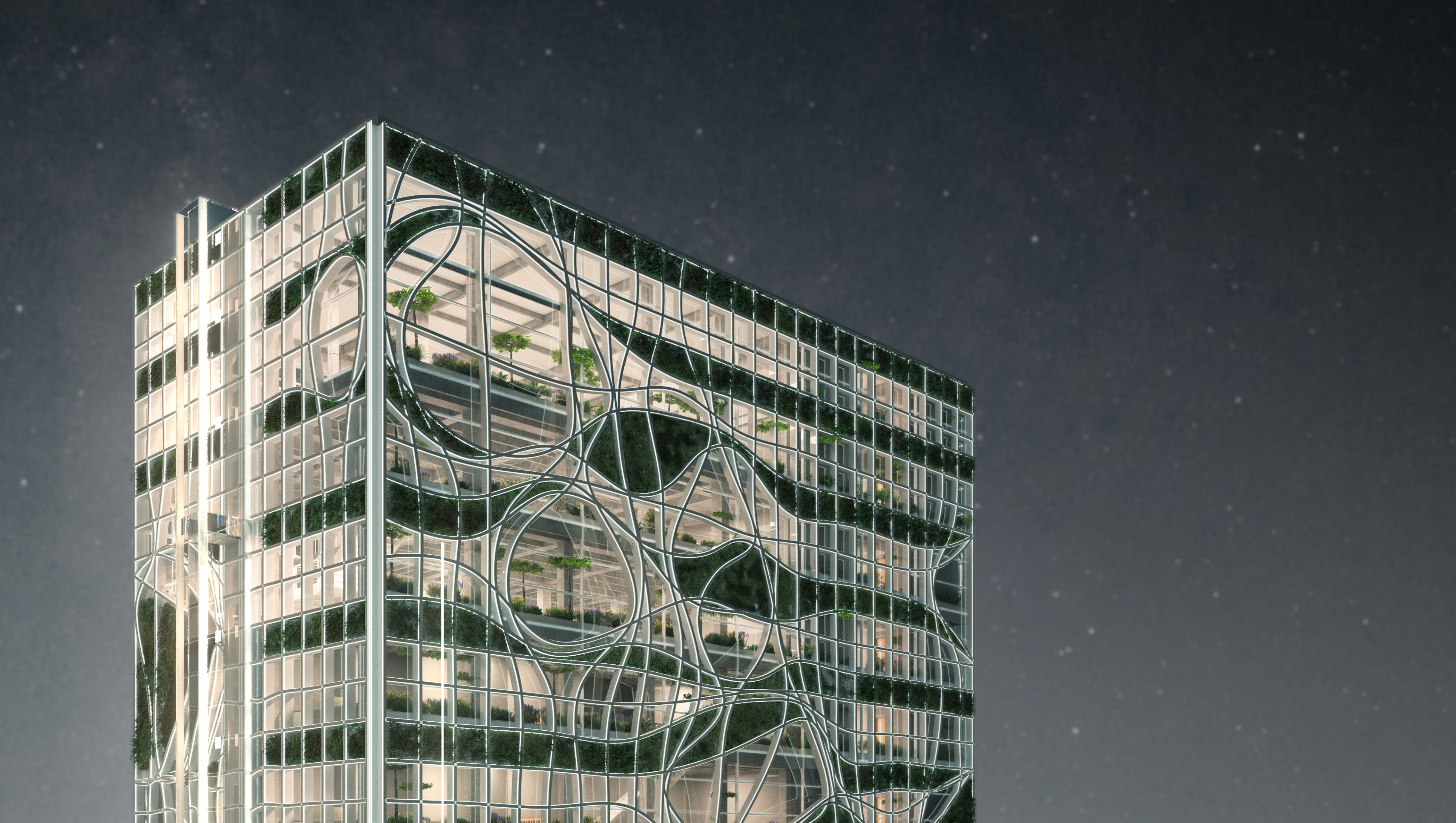

As a motif, the metal fascia here represents a breakthrough among the listed models, which are interwoven in the composition of Copper House 2. It is needless to explain the enormous artistic superiority achieved by Radić in comparison with the often used practice of coating facilities today.

Testimonies of this overlap have been very clear since his early renditions. The names of his buildings also indicate a deep respect and the aesthetic of the design process. The Casa de Cobre, the first step in his works, dated 1999, is an early indication of what Smiljan would accomplish designing the Copper House 2 a few years after. A confusing conclusion is made of completely opposite elements integrated into individual sets that will become the main feature of Smiljan’s work – vertical wooden joist, convincing use of façade coating and a peculiarly emphasized, illogical construction element.

In the case of the Copper House 2 from 2005, the initiation made by the Casa de Cobre, Smiljan masterfully shapes into a filigree exhibition of all the distinctive architectural elements of the house we inherited from the 20th century. As if the Copper House 2, fully aware of it or not, has borrowed and in the finest manner used a handful of less, or more obvious details, presented altogether in a completely independent structure which hides these elements, revealing them only to connoisseurs, while in its final appearance, it uncovers itself to others as an example of undisputed aesthetics.

There, all of the positive traits of early modernism are mixed, excessive dynamism, almost desert-like peculiarity and the explicit emphasis on the use of modern materials, while the entire narrative (poem) is complemented with the imagination of a postmodern stroke enriched with ironic elements. If slender white profiles and the deck-shaped form of one side of the building, as well as its entire striking appearance, are clear allusions to the Farnsworth House, then the quotes outlined above, mild irony and self-awareness definitely originate from the Vana Venturi House. It is sufficient to mention the diagonal elements of skylights or windows, so distinctive in both cases, that one gets an impression as if Smiljan, out of his most persuasive conviction, pays tribute to the leading figures of the last century, simultaneously expressing a tremendous architectural erudition, sublimated superbly in his own expression. The latter does not at all have to be a result of author’s conscious principles, nor of his volition, nevertheless, the stated assumptions are ultimately recognized.

Chilean House, 2006

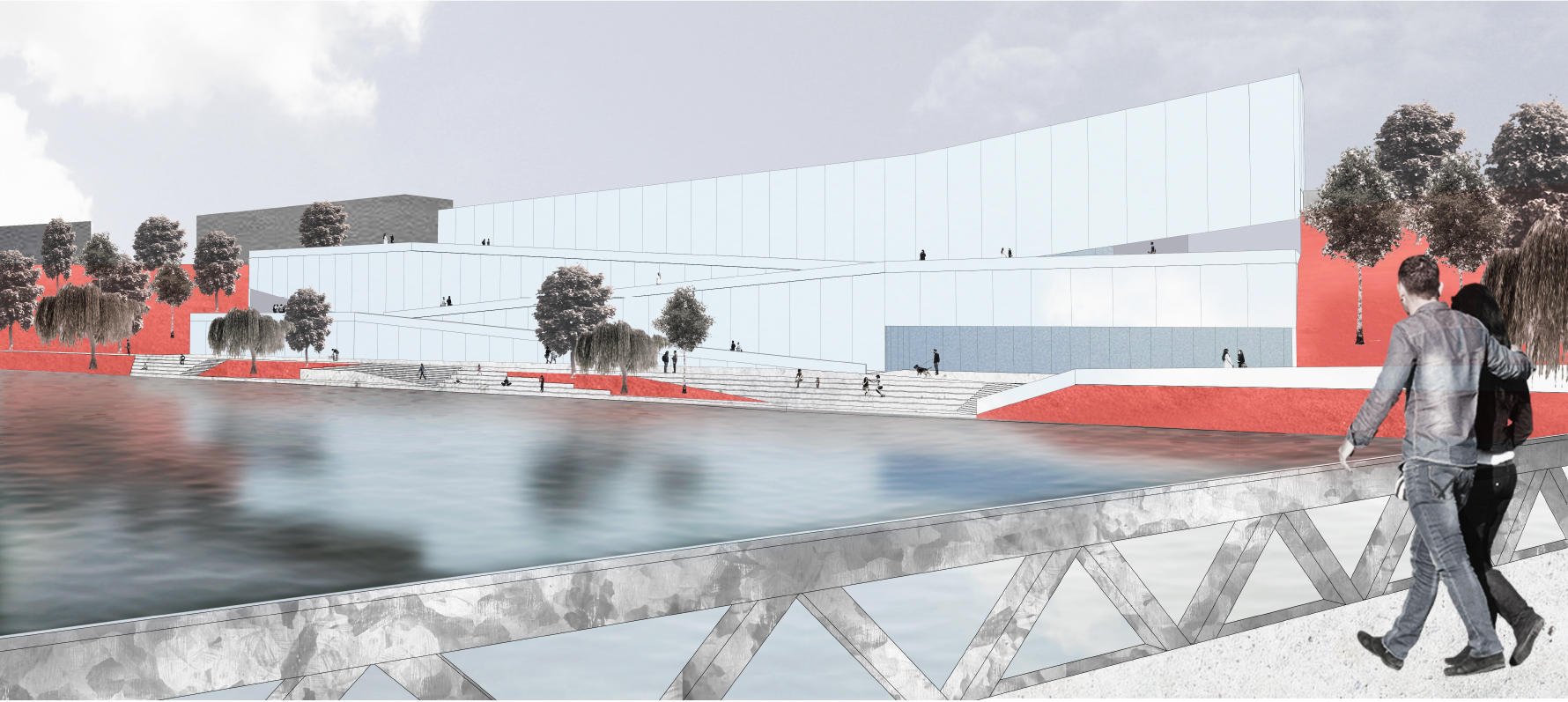

Even in case of the Chilean House, the most exemplary models of high European modernism, appear in a special form of juxtaposition.

Where a subdivision of the base was necessary, the courtyard is shaped by the wall. The impression of an atrium is accomplished in the way of the living space of the house being contrasted to the wall-torn mantle of nature. The achieved counterpoint of the building’s transparent side is brushed up in detail by the rectangular opening in the surface and vice versa, the heavy curtains behind the large glass surfaces completely dampen the impression of transparency, if drawn. The aforementioned counterpoint makes an additional tonality in relation to slender, in cross section circular, steel columns appearing with eleganc with the removed glass surface.

The next big step in his practice is the Chilean House, dated 2006, with which Radić shows already acquired maturity, but now closer to the earlier epochs of Modernism. Namely, all it’s elements developed through the turbulent first half of the 20th century reside firmly within a form so recognizably typical for South America, or its Pacific side. If one could place in his imagination the Villa Tugendhat at any slope of any European city, then the Chilean House can be located and experienced only within the context of the special scenery of the Andes. Yet, through the prism of Smiljan’s work, they are presented and accepted globally. The Chilean House is indeed a good example of intimacy between the architect and the overall ambience surrounding him, the one that the architect has been, consciously or not, living through since his earliest age.

The scope of Smiljan’s accomplishments do not substantially diverge from the above stated, it is only in dependence of the character of the program and of the specificity of the environment that they trace singularity, always so special and distinctive. In that way, a man, regardless of his expertise, is outrightly attracted by forms, like the ones on following projects: House for the Poem of the Right Angle, House A, Mestizo Restaurant, Zwing Bus:Stop, and through a variety of renditions, studies and models, dragging him at the same time into the contemplative relationship to a cliff, a pasture, a boulevard, a square, a clearing in a for forest or any environment they reside in.

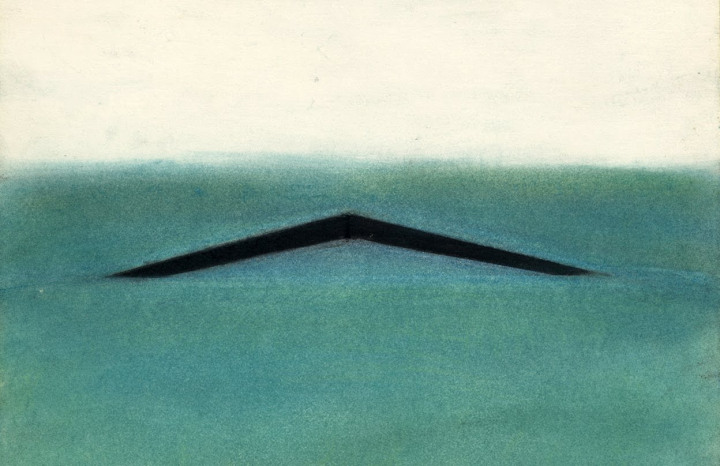

Such a multifold feeling prevails through stages experienced by future regional theater project in the Biobio area, which was selected as the winning entry in a competition conducted in the early 2000s. It appears as if Smiljan wanted to calm down, not to anchor the Noah’s Ark by no means in the completely turbulent and wavy architectural atmosphere of the early 21st century, handing it over to the contemporary generation for use. Multifold in the sense that all stages of presenting a rather bold form intended for a public-purpose building, represent also the final aesthetic manifestation, not a mere step towards the realization of the construction – a model of building with structure presented in wood; representations of building in a way in where the experience borders the serenity of the restless, resembling a certain Italian master of the early 20th century. If young Edouard Jeanneret was fascinated by the aesthetics of a passenger ship, recommending and using it after the World War II, then Radić feels empowered to breath in mythological illusions into inherited dogmas of high Modernity.

Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2014

Even though at an early stage recognized and accepted by most critics, colleagues, and among the professional circles, and despite unprecedented individuality of his expression electing him a professor in elite international schools of architecture, the placing of order of Smiljan’s vision for the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, annual honor bestowed upon the most established architectural creators from the world, brought him an award from the wider part of the audience, respect and special treatment for his earlier works. The diversity of the modern act, at that time turning sterile and predictable, is crushed by the vision of the park surface in front of the Serpentine Gallery which brought the sensibility of the Mediterranean myth to it and simultaneously reinstated that myth symbolically at the European soil.

Teatro Regional Del Biobio, under construction

Had it remained an unimplemented idea, the entire block of drawings and the model itself would remain a witness to Radić’s extraordinary idea that routes simultaneously both the future and the past. To be compared to the Vidovdan Temple by Ivan Meštrović.

Unlike the architecture of more purpose-wise specific facilities he carried out, Smiljan here traces his own path as the path, not just of cultural heritage, but of a far more complex one, of an environment contemplated on his own with a clear origin. Here, the concept of organic form is enriched by the organic splendor of materials while the form itself is biological, treated as a shell, cocoon’s membrane or even as a cluster of different materials that animals accumulate as a residence or simply discard. All of that from the foundations – and foundations of the structure are carelessly laid down, rough, yet slender boulders – reverses the previous solutions emphasizing the readiness of the modern man to seek counsel in a certain type of super-modern myth of perfect materialization. As if Smiljan’s pavilion is not too overwhelming both as an experiment and an expression of the revolutionary use of materials, while it stands lent onto something clearly representative of the South American monolith, snatching the primacy from the prehistoric, precisely at the spot where the European prehistoric heritage is the most obvious.

The vast erudition presented through extraordinary subtlety and a strong sense of intimacy towards the environment that has been derived from universal respect for the environment that surrounds it primarily give strength to Smiljan’s authorship, by which he already became globally respected, and whose achievements we are yet to discover.

Mirza Mehaković, M.Arch.