Today it is believed that the architecture and construction are largely governed by investors and that an architect has the role of a mere drawer. Besides private investors, the largest investor is still the state and therefore the architecture and urbanism are largely influenced by the policies of the rulers. Is this just a byproduct of the system that emerged after the breakup of Yugoslavia, or it has roots in previous periods? In order to understand the incomprehensible behavior of today’s authorities, it is necessary to examine the relations between politics and architecture through history on the territory of today’s Bosnia and Herzegovina.

One of the most decisive moments in history of Bosnia and Herzegovina happened after the war in Yugoslavia when the state got a new political arrangement with three constituent ethnic groups, two entities and a joint presidency. This discriminatory system of presidency excludes the possibility of equal participation of other nations in the governance of the state, and is currently strengthening nationalism of the three constituent ethnic groups who are struggling to spread their influence. The state is clearly ethnically divided, and the success and justification of war events is further enforced by three different authorities by masking or destroying the heritage that belongs to all the inhabitants of Bosnia and Herzegovina, taking away common areas and objects and allocating them only to one particular group of users. Such surfaces must remain open, neutral and universal; such spaces are common and belong to all users who live in those cities.

Widespread masking of history and facts has been launched, a selection of what is right has been made, what should be rebuilt or destroyed. A special emphasis was put on the construction of cheap and unimaginative ethno and not so much ethno objects. “Older and more beautiful” buildings were made, and the spirit and importance of the original ones was destroyed by non-creative painting. Sometimes these are important objects such as Skenderija in Sarajevo, and sometimes less significant ones such as multi-storey apartment buildings in the center of Bijeljina, formerly known as “Kata, Nata and Fata”, and today only known as “the white buildings”. In addition to the rich historical heritage of Bosnia and Herzegovina, thematic parks like Andricgrad (Andric city) are built, whose architectural value is almost non-existent.

Today’s Bosnia and Herzegovina owes its rich historical heritage to its geographical position, which always represented the border of cultures between “West” and “East”. Land borders of states are almost always areas characterized by heterogeneity of the population, religion and culture, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, being the border between the west and the east, is heterogeneous not only in the border areas but throughout of its territory.

The first significant period in the architecture of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the past 600 years was in the middle of the 15th century. The Kingdom of Bosnia in 1463 fell under the rule of Ottoman Empire, which allowed the preservation of Bosnian identity, but with new socio-political changes this identity gradually started to disappear. The government favored the population that converted to Islam, and that is why Bosnia and Herzegovina ceased to be just a border province and experienced a period of progress. New cities were built along the rivers and at the crossroads of routes that became the centers of trade, and a large number of residents of Bosanski Sandzak left a deep trace in the cultural and political history of the Ottoman Empire.

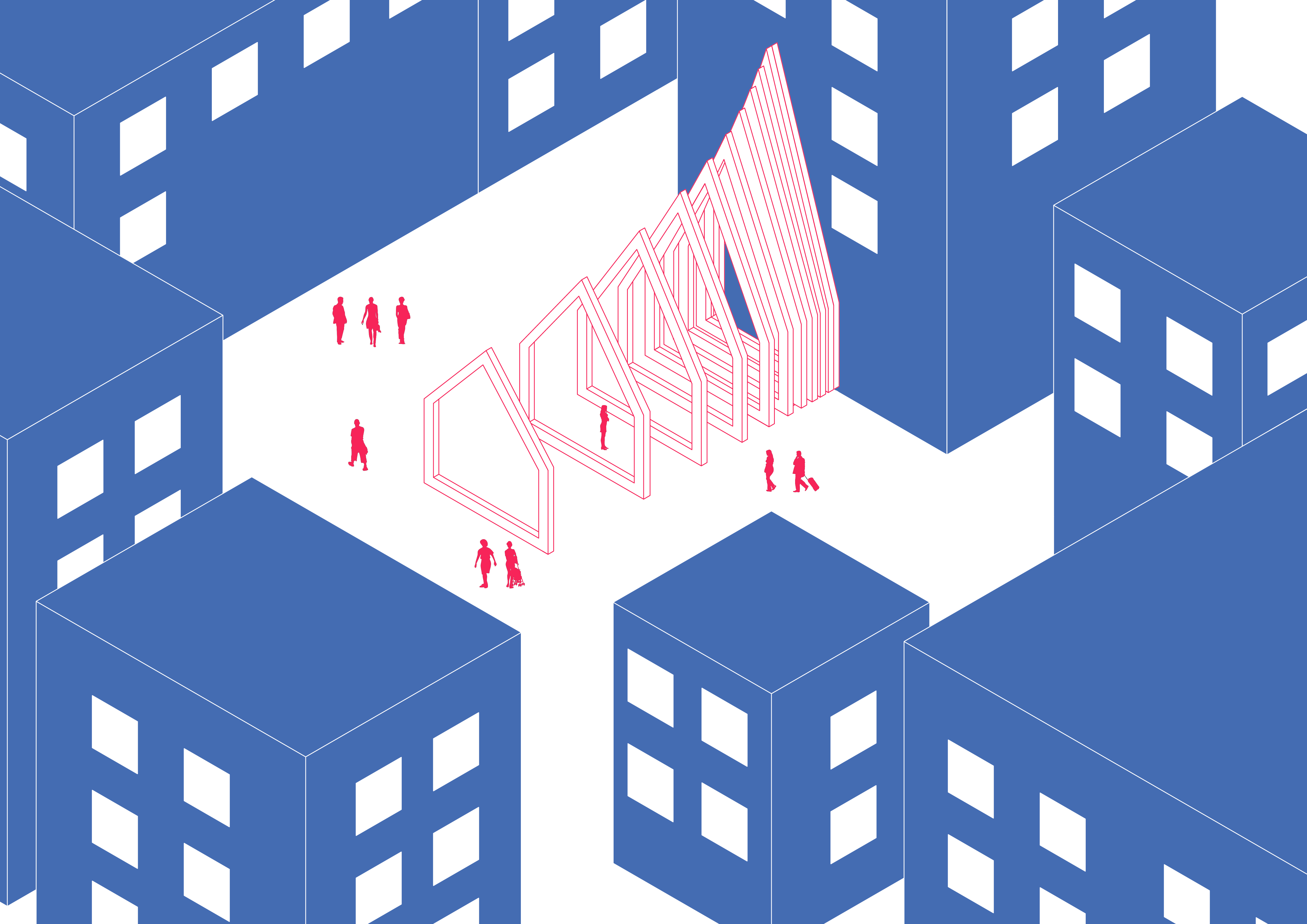

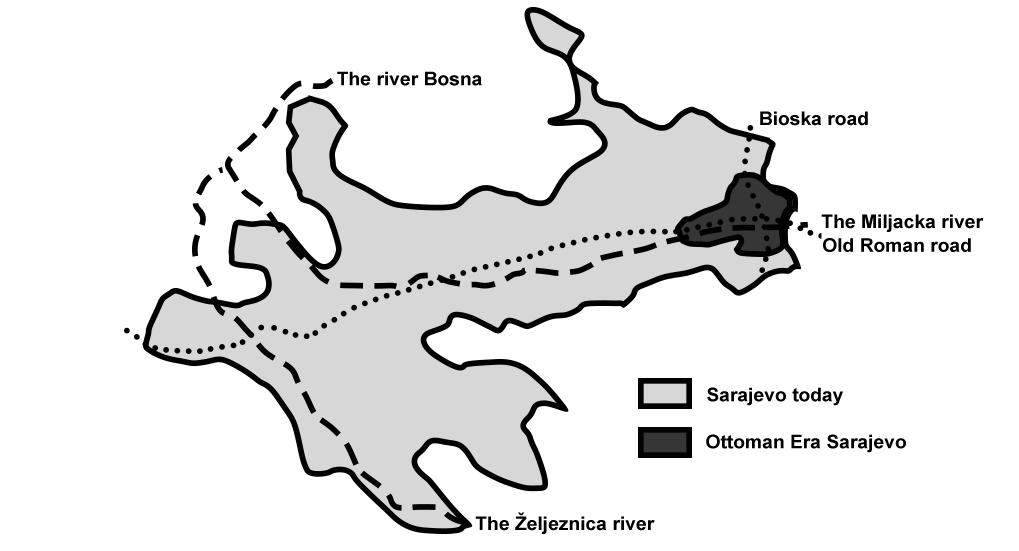

lmage 1 – Sarajevo during the Ottoman Era and today

Sarajevo as the most important settlement was twice the seat of the provinces Sanjak of Bosnia and Bosina Vilayet after major territorial reorganizations. In addition to the capital, other new cities were built as traditional Ottoman settlements consisting of mahallas and carsija (bazaars). Mahallas represented housing settlements that were organized by ethnicity or by some other criteria such as the level of education and profession. A bazaar (carsija) was the central city core consisting of craft workshops, shops, mosques, fountains and it was the economic center of the city where the most of the economic activities were carried out. Although the Ottoman bazaars (carsija) were clearly defined in their content, in Bosnia and Herzegovina these rules were changed in order to support and control the local population, and the construction of other objects of sacred architecture was permitted. In addition to the mosques, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, churches, synagogues and clock towers were built. These buildings testify to the policy of the Ottoman Empire in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which sought ways to gain support of the local population.

The street network of the settlements was irregular, regardless of the configuration of the terrain where it was created, which was typical for cities established during the Ottoman Empire. In the middle of the XIX century, in the plain areas along the right bank of the Sava River, new settlements with a street network appeared, which was not common in that period for Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bosanski Samac and Orasje are the two largest cities that were created as a result of geopolitical changes in that period.

Image 1 – A typical Ottoman town with an irregular street pattern

After the conference in Kanlica in 1862, the exodus of Muslims from the Principality of Serbia to Bosnia and Herzegovina was ordered. It was necessary to establish new cities in order to accommodate a large number of refugees who demanded a large compensation for their lost property in Serbia. The sultan at that time was Abdul Aziz, who used this as an opportunity to strengthen the borders towards the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, which started to represent an increasing threat to the Sanjak of Bosnia and the Ottoman Empire. New settlements were formed against existing Austro-Hungarian settlements just on the other side or the Sava River bank, which at that time represented the border between east and west. Since the evolution of urban forms does not exclusively depend on the needs of the users of space, it is often a consequence of political interests of the authorities, so the formation of these settlements was solely driven by the desire of the sultan for the formation of new modern cities.

Liberal politics of sultan Abdul Aziz opens the door to European culture and it slowly begins to penetrate the Sanjak of Bosnia and marks the beginning of the downfall of the Ottoman Empire in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This is mostly reflected in newly formed settlements where refugees from the Principality of Serbia are housed. Sultan Abdul Aziz forms two great cities and gives them the names of Upper and Lower Azizia and builds large mosques in them. These cities today bear the names Bosanski Samac (Upper Azizia) and Orasje (Lower Azizia), and their street network is atypical for Ottoman cities.

Image 2 – Bosanski Šamac

Image 3 – Orašje

Influenced through policy of Abudl Aziz, the new cities do not resemble other Bosnian settlements, and in their urban structure they lose the identity that was built over the previous four centuries. These settlements do not contain characteristic urban entities such as mahallas and bazaars, instead the Upper and Lower Azizia have the appearance of cities built in Western culture, and the only thing they have in common with the Ottoman Empire are the mosques built and named after the sultan Abudl Aziz. In addition to these two towns, several other settlements were built, and one of them was Brezovo Polje, which also has Aziz’s mosque built in a non-characteristic neoclassical style.

The reasons for such building policy date back to centuries ago. According to the legend, sultan Abdul Aziz’s grandmother Emi (Aimée du Buc de Rivéry) was a cousin of Empress Josephine, wife of Napoleon I and was allegedly kidnapped near Martinique and sold to the harem of sultan Abdul Hamid I, who married her. Emi promoted French values and liberal politics in the Ottoman Empire, and her grandson Abdul Aziz was the one who implemented them. The fact remains that the sultan Abdul Aziz was the first sultan who visited Paris, and after that, impressed by the French architecture, ordered the construction of several buildings of that style in Istanbul. In addition, he brings French urbanists who will form new cities along the right bank of the Sava river, Upper and Lower Azizia.

Image 2 – Sultan Abdul Aziz visiting Paris

After the downfall of the Ottoman Empire in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy came to power. The new government is faced with the strong presence of Ottoman culture and strives to remove it in order to gain the confidence of the local population as quickly as possible. Because of the complex situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the dual monarchy decides that the best solution is to create a new national identity, and architecture was just one of the instruments in achieving it. The demolition of the existing and the adoption of European architecture did not seem to be a good solution, as it could lead to the indignation of the population who were under the influence of Islamic way of building for 400 years, which is why the Austro-Hungarians decided to create a new Bosnian style in a very short time.

The formation of cities was completely in the service of politics during the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Reducing the influence of Ottoman, Serbian and Croatian culture could be achieved by creating a unique Bosnian nation which could be easier controlled than several smaller culturally diverse groups.

The first interventions in the area were the expansions of existing street profiles as well as the introduction of some new roads. For the needs of the construction of Sarajevo, Austro-Hungarians hired architects and urban planners of Slavic origin, educated mainly in Vienna, thus creating an impression that the Bosnian ideology is not imposed from the West, but an original Slovenian thought. By expanding the traffic network, the city occupies a larger area and the construction of new prominent buildings in the main streets begins. This type of intervention also appeared in Rome in the 16th century when the Pope ordered the extension and introduction of new streets to increase the importance of the buildings belonging to the church. The task of such interventions is not only to improve the traffic infrastructure, but also to increase the political control and importance of the city. It is interesting that the enforcement of power and control was not carried out by military means, but through administrative civil institutions.

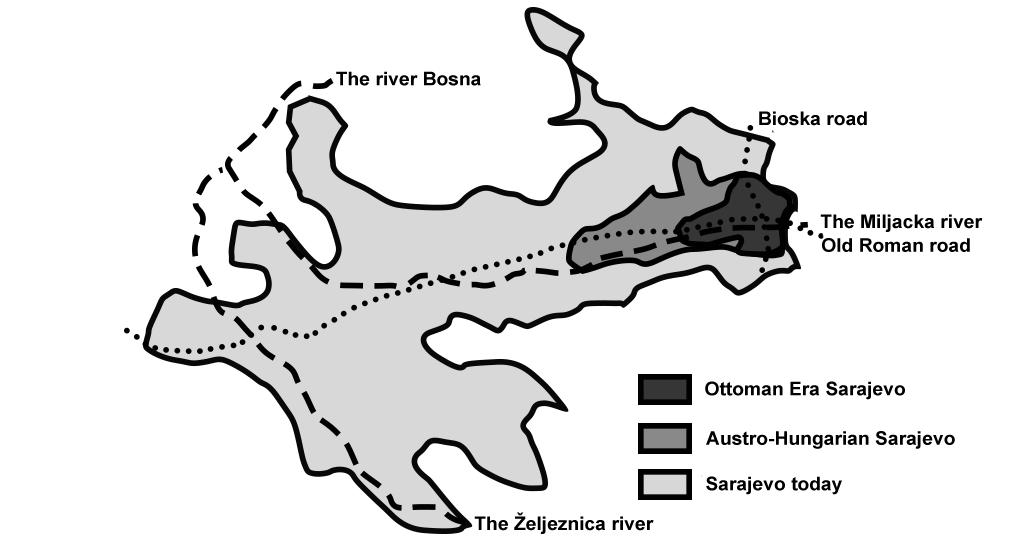

Image 3 – Sarajevo during the Austro-Hungarian Era and today

Politics and the change in the significance of some urban units is best seen through the case of Bascarsija (Old Bazaar), which, with the arrival of Austro-Hungarian Empire, completely loses its role of an economic center of the city and gets a new role of a historical district, thus becoming a symbol of “past-time.” Besides losing its importance, the Old Bazaar also loses its original appearance after the fire in 1908, and through the reconstruction planned by the Moravian architect Josip Pospišil Old Baazar (Bascarsija) loses several buildings and gets new streets. Pospišil demonstrated a strong desire for the introduction of modern European theories in Bosnian architecture. This attitude towards inheritance is a consequence of an attempt to create a new identity through smaller interventions in space that do not have to be obvious, but they change the original form of urban entities.

Another attempt to separate Bosnia and Herzegovina from the legacies of the Ottoman Empire, Serbia and Croatia is to create a Bosnian style which was introduced when new facilities were designed. The purpose of most newly built buildings was the promotion of Bosnian nation, and the buildings of the Social Center (Drustveni Dom) (today’s National Theatre of Sarajevo) and the City Hall are the most interesting examples. The buildings are constructed as free-standing buildings that occupy the entire block and thus represent the most important buildings in the city. Such examples also appeared in Berlin in the 19th century, according to Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s plan. He strategically positioned the most important buildings, occupying the entire blocks, thus increasing their significance.

Image 4 – The City Hall in Sarajevo

The City Hall in Sarajevo is a freestanding building which, as such, had a task to mark a separation from the present times and represent new values and ideas in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The original project for the City Hall building proposed by Parzik was in neoclassical style, but to the Bosnian governor Benjamin Kala (Kállay Béni) pseudonymous architectural style seemed to be the perfect tool for implementing the ideology of Bosnian nation, so architects Alexander Wittek, and Cyril Ivekovic were hired for the task. The pseudonymous architectural style is considered to be the predecessor of the so-called Bosnian style, which was first defined by Josip Vancas. This style never became popular, and the reason for this could be the brief rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in this region. The Social Center building by Karl Parzik’s project is also a freestanding object, but it does not belong to the Bosnian style but to Neo-Renaissance style and it is a copy of the Vienna Opera House. The goal of Social Center was also the creation of new national identity, not through the style of building, but through the purpose of bringing together all cultures and religions under one roof and thus minimizing their influence.

Image 5 – National Theatre in Sarajevo

For the first time, such a plan was successfully implemented at the end of World War II in 1945, when Bosnia and Herzegovina became one of the six socialist republics within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The main idea of this government was “brotherhood and unity,” describing the equality of all peoples and nationalities in socialist Yugoslavia. The idea of fraternity and unity was to be imposed upon culturally heterogeneous population, with the same goal as all previous governments, which was easier control and governance of the state.

By building factories, settlements and with increasing population, the need for greater electricity production rose. New thermal power plants were opened, and one of them was in Ugljevik, which already had a functional coal mine. The construction of a thermal power plant increased the consumption of ore, which led to the expansion of the mine’s surface excavation. In the process, most of the surrounding settlements were completely destroyed, and the population had to be moved to a new location. Thus, in the plains of the village Zabrdje, 3 kilometers away from the thermal power plant, in 1980s, the modern Novi Ugljevik was created, which received the international award for urbanism in the 1980s.

Image 6 – Ugljevik

The newly built settlement becomes a representative example of state power, and the factory’s chimney 310 meters high, becomes the tallest building in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the third in Yugoslavia, the eighth in Europe and the 15th in the world. The cult of the ruler was promoted through the architecture and symbols, thus the inscription “Tito” stood on the chimney and could be seen from the settlement. With the modern design of the city, a clear message was sent to the inhabitants, the message of complete break with the past, and with clearly defined urban plans it was no longer possible to introduce local elements into the construction and it was only done by few architects. This system suited the socialists, all the cities were similar, and the identity of the local population was lost.

Image 7 – Ugljevik today

Thus, urbanism and architecture were once again tools of the ruling classes that controlled public opinion, by raising and lowering the significance of certain buildings and urban spaces. The characteristic of all interventions in the space that were in the service of politics is erasement of historical periods that did not correspond to the ideology of the current government. Such understanding of cultural heritage is a sign of ignorance, and it has been shown through history, that architecture in the service of politics does not provide long-term authority in this region.

By analyzing several historical periods in Bosnia and Herzegovina with different ideologies, it can be concluded that town planning is almost always in the majority in the service of politics, but it can also be seen that the authorities always had a kind of respect towards the profession, and therefore, today’s influence of politics on architecture is worse than ever, in the history of Bosnia and Herzegovina.