author: Josipa Slaviček

Year 2017 was marked by the 20th anniversary since the opening of the Guggenheim Museum, located in Bilbao, northern Spain, in the Basque province. Architects-representatives of the continent, Arata Isozaki from Asia, Frank O. Gehry from North America and Coop Himmelblau from Europe, were invited to the contest. The project’s goal was to propose a visionary concept of a new museum that will change the city’s image, hoping Bilbao will become the new Sydney. Gehry, who won the competition, claims to have been invited to the competition to create an architectural work that will stall the city from dying, a new Sydney Opera House. So he came up with the convulsive, majestic, climactic assembly of titanium and stone, of heft and shimmer, a cross-breed of palazzo and ship that also flips its tail like a jumping fish, that now stands on the banks of the river Nervión.

With this solution, Frank presented the Guggenheim Museum as an architecture that is understandable to everyone, not just architects and others who understand its complex and to the naked eye invisible expression, but to passers-by and tourists who will notice its size and glitter as an ideal postcard background to send to family and friends from their trip. Though there were no social networks in that time that would later spread the news that the world has gotten a new Instagram destination, the city gained its popularity the first year. Since the opening in 1997, 7 million museum visitors have been recorded, of which 60% were tourists. The city had become a new tourist destination, with the help of a new urban phenomenon called the Bilbao effect that aims to economically grow cities by combining cultural investments and by building one thriving architecture. Having seen success in economic terms, other cities wanted the same effect. In 20 years, almost every major city has created its own Bilbao effect hoping that it is an instant remedy for areas that have faded, brownfield areas that needed ‘RE:’ (regenerate, revitalize). They wanted their city to become a cultural destination with great architecture that would be the new city icon. As a consequence, every cultural institution of today feels the need to be the one responsible for the transformation of the city with new architecture as if it were alchemy.

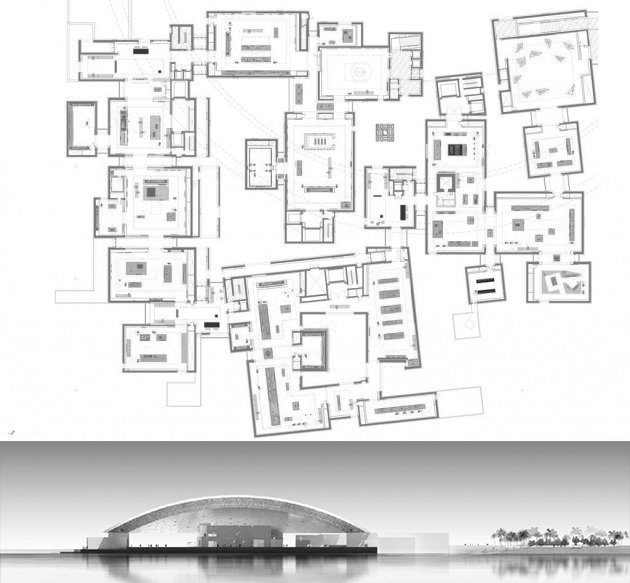

What is undoubtedly questioned is whether the Bilbao effect is actually a myth? Aren’t there many other cities that were the subject of a similar scenario even before Gehry? Bilbao was not the first city to be transformed by an architectural piece as an icon. This could have been the Sydney effect or Pompidou effect as both cities, Sydney and Paris, have become a different cultural destination of their time with the new grand architecture. Although Paris was a world renowned cultural city for the sake of its history, Centre Pompidou, apart from being a top architectural work, changed the way of thinking about cities’ public space. However, the Guggenheim Museum has influenced further thinking about architecture as a sculpture, creating a tendency to invest heavily in the experience, size and glamour of the building exterior that would be a new, today Instagram worthy, background. In addition to the need to recognize the size and shape of the building, there was also an inclination to combine the specificity of famous museums from different cities and time periods to create something ”new” and ”unique”. For example, the concept of Louvre Abu Dhabi was based on combining the Bilbao effect with the exterior and exhibition setup such as the Louvre Museum in Paris in the interior.

Thinking about the new economic opportunities that the new building could bring, the city’s background story was forgotten, its urbanism that could bear the Bilbao effect. Sydney and Paris had a century-long tradition of transforming the city before the Opera House and Pompidou. Before the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao has been thinking about infrastructure and public spaces for 10 years, wanting to create a city firstly for people and after for tourists. The museum was actually the last piece of the puzzle of a deliberately designed network of functions that created a powerful foundation for further development of the city. Nevertheless, after 20 years of its title as a popular tourist destination, new urban and sociological problems have come to light. The city’s tourist capacity planned within urbanism 30 years ago no longer corresponds to today’s needs and foreseen population growth figures and tourists. Bilbao became a dual city with high standards in its ‘downtown’ with Guggenheim Museum in the focus, and ‘old town’, a former center of the city, which is today a periphery whose majority of the population is poor. Statistical data confirms it: Since 2000, the city has registered a 33% increase in poverty, mostly due to the rise in real estate prices, with the result of the displacement of the population in the periphery. So the city was once again at the beginning of a story in which the main theme was the dying city, or in this case its old historic center.

Apart from the fact that, in the example of the city from where it had begun, it has brought negative consequences, or that architecture avowedly became a sculpture, the Bilbao effect has, intentionally or not, brought a change in urban planning. It also created generic cities of stand-alone buildings in which the craving for uniqueness is blurred in the heaps of semi-recollections. Middle Eastern cities, risen from the sand, have become mutual copy-paste; revitalized waterfront areas have become synonyms for the architectural work that will be the icon of the city. So for example, Singapore looks like Taipei, that looks like Dubai, that looks like Doha, that looks like London Docklands. The fact that the Bilbao effect method exists today is confirmed by the Elbphilharmonie Concert Hall project in Hamburg designed by Herzog & de Meuron, which opened its doors to the public in 2017. Hamburg, one of the leading port cities in industry and shipbuilding throughout history, is now being promoted as a city of culture once again with its new, unique, magnificent architecture whose symbol it has become. The concert hall is located at the intersection of the old city center and the HafenCity project of the brownfield zone revitalization into a new city center that has created a new waterfront image. The entrance to the building is still free and visitors are allowed to reach the central floor with a cityscape view. Despite the fact that the construction of the building greatly exceeded all set deadlines and the budget, and after the first concert was criticized for the bad acoustics of the concert hall, it became the new main tourist attraction and a new Instagram background of the city. Just as the city of Bilbao had been looking forward to the new economic opportunities 20 years ago, Hamburg hopes for it today. And whether the city of Hamburg will become a proven example that size doesn’t necessarily produce quality, just as quality should not be featured with its size, and that the result of a short-term effect usually produces a long-term defect, we will obviously find out in 2037.

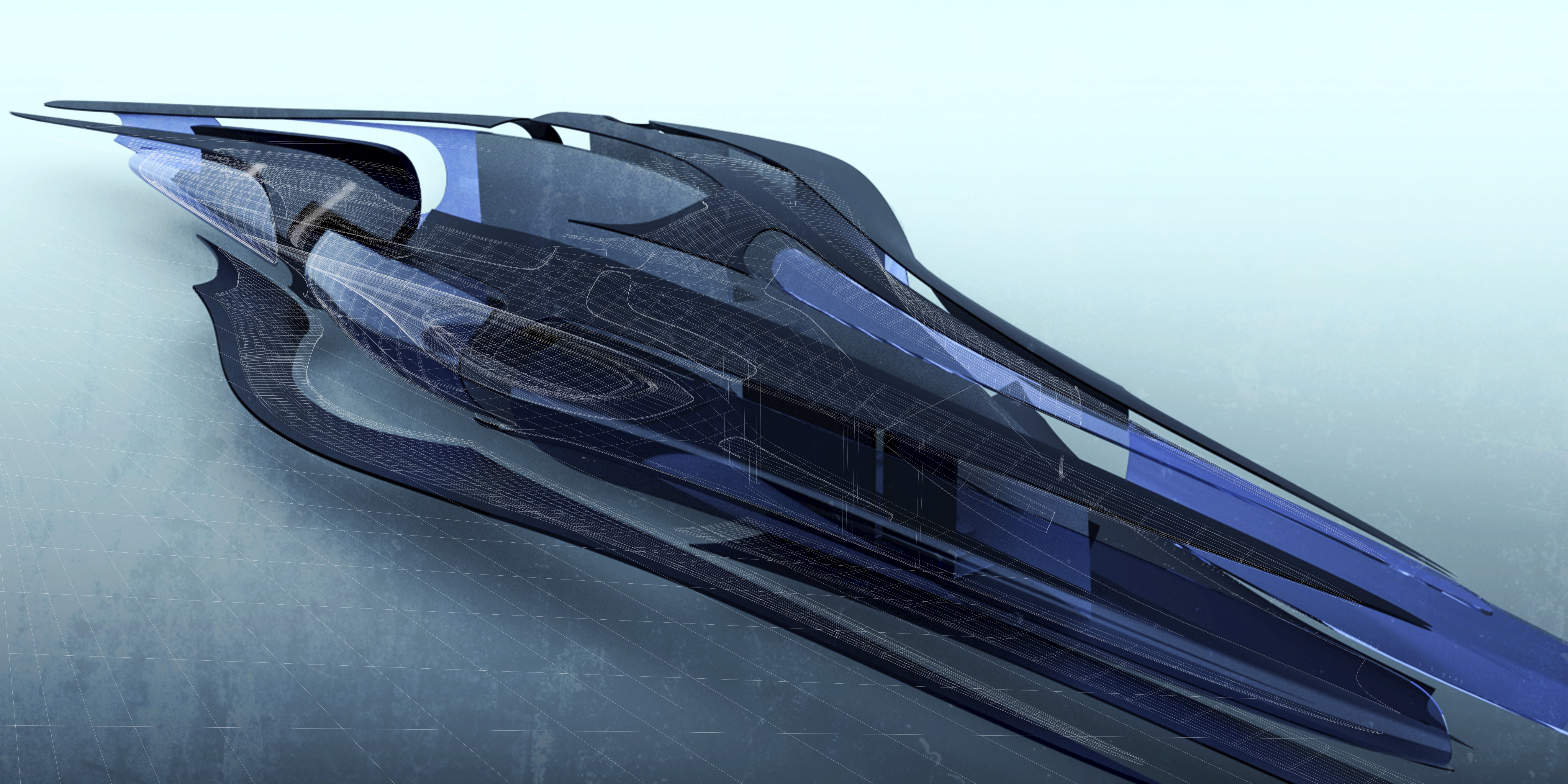

top image: Architecture as the game of chance (Josipa Slaviček)