Change is the only constant — unless you’re awaiting the return of Emperor Constantine.

author: Sotiris Frankos, Athens, Greece

“God is dead; but given the way of men, there may still be caves for thousands of years in which his shadow will be shown.”, Friedrich Nietzsche

When Nietzsche posited that god was dead, what he meant by it was that mankind in a post-Enlightenment world seemed to have realized that the universe was not governed by divine providence. God became a superfluous concept for a functioning society. Governments could now be of the people, by the people, for the people, rather than chosen by divine right. Morality was no longer seen as objective and imposed top-down since the provision of a moral framework was possible through philosophy.

Religious institutions have always been largely, if not entirely, prescriptive rather than descriptive in matters relating to their function; that is to say, they describe how something must be, rather than describe how it tends to be in most of its manifestations. The inevitable traditionalist approach to everything cannot but affect religious architecture as well. It’s always been this way.

Or has it?

Well, not exactly. Churches have always been places of worship first and foremost, and religion is rightfully not considered the most progressive of cultural forces. They have largely lost their central role in an individual’s life in contemporary Western culture, but at one point they used to be social spaces bursting with life, or even places to stop and sleep at during one’s pilgrimage. These secondary functions, while never usurping the primary religious one, were important and not ignored, and taken into account in the way the churches’ interior was organized.

For example, back when pilgrimages became a major religious trend in Medieval Europe, the bigger Romanesque churches functioned not only as places of worship for the locals but also as places of attraction and stops in a larger journey. Extra aisles were sometimes added to the church plan for pilgrims to stay overnight in, providing the pious passersby with shelter. The outer walls were lined with objects of religious worship, and through the introduction of the ambulatory that housed the most important of those objects and sometimes spatially acted as an extension of said aisles, church plans presented a quasi-museological approach entirely consistent with their role in their cultural context.

Much more pronounced were the changes in church architecture that were dependent on each culture’s technical ability and available materials. The introduction of load-bearing trusses allowed for changes to the temple’s form by making it possible to create significantly larger openings. This had remarkable effects to not only the form of the building, but by letting in substantially more light it produced an entirely different atmosphere in its interior as well. By making the appropriate adjustments, like introducing elements that drew one’s gaze upwards, making the openings radically more elaborate in shape and introducing stained glass, this atmosphere was fundamentally different than the one of Romanesque churches, but no less transcendental.

Gothic church interior. Photo credit: Thomas Millot

As a matter of fact, while the Church as an institution has been considered socially conservative for the largest part of its existence, culturally it hasn’t always been so. It used to be at the forefront of architectural and artistic innovation. New art styles and building techniques were developed in direct association to it. Before the Renaissance, art and architecture were hardly ever a matter independent of public life, and religion used to be at its center.

Of course, the Eastern Orthodox Church never went through the Rennaisance. Nor did they ever adopt the Gothic style or any other innovation in church architecture introduced in the West after the Great Schism in 1054. That’s not to say its places of worship have remained exactly the same in the entirety of the past millennium, but the adjustments have been minor in comparison.

In the contemporary world, it would not be a reach to say that in matters pertaining to a temple’s form, Eastern Orthodox church architecture is flat out mimetism. It takes a form developed largely as a result of the structural requirements imposed by materials and technology of an earlier time and completely casts it in concrete. The resulting monolithic structure looks like the older churches on a surface level, but there is no underlying honesty or logic to its form.

It reproduces a typology that aimed to create a specific kind of atmosphere in its interior, attempting to channel the transcendent and the sublime, and completely disregards it by introducing imposing and not at all discreet, and often very luxurious, chandeliers. This is dissimilar to the Gothic example presented above; change is inevitable, but it seems as though no attempt has been made here to retain the transcendent atmosphere through a redefinition of what it means. It is not a graceful adaptation to today’s culture — it is the result of an institution that abhors change trying to adapt by making the smallest adjustments possible in the material sense, and failing to understand their immaterial implications.

Were all that to have been done consciously, the resulting architecture would border on postmodernism with the way it reproduces elements after having completely stripped them of their original purpose or meaning. It is like assigning someone who has not read a single book of poetry in their life to write a poem. I expect the result to be something that looks like what a poem is supposed to be like — meter, rhymes, flowery language — but simultaneously lacking an elusive yet fundamental quality.

And here’s the thing — the Bible does not really concern itself with architectural matters. God has not specified to any large degree of specificity what their home should look like; there is no word of god dictating this disaster, it’s entirely man-made. I am not calling for a radical redefinition of what a church is, architecturally speaking, though I do have to admit it would not bother me in the least. I am calling for the realization that the nave, the aisles, the dome, the apse, are all concepts that can manifest and combine in innumerable ways. They just have to be allowed to, first.

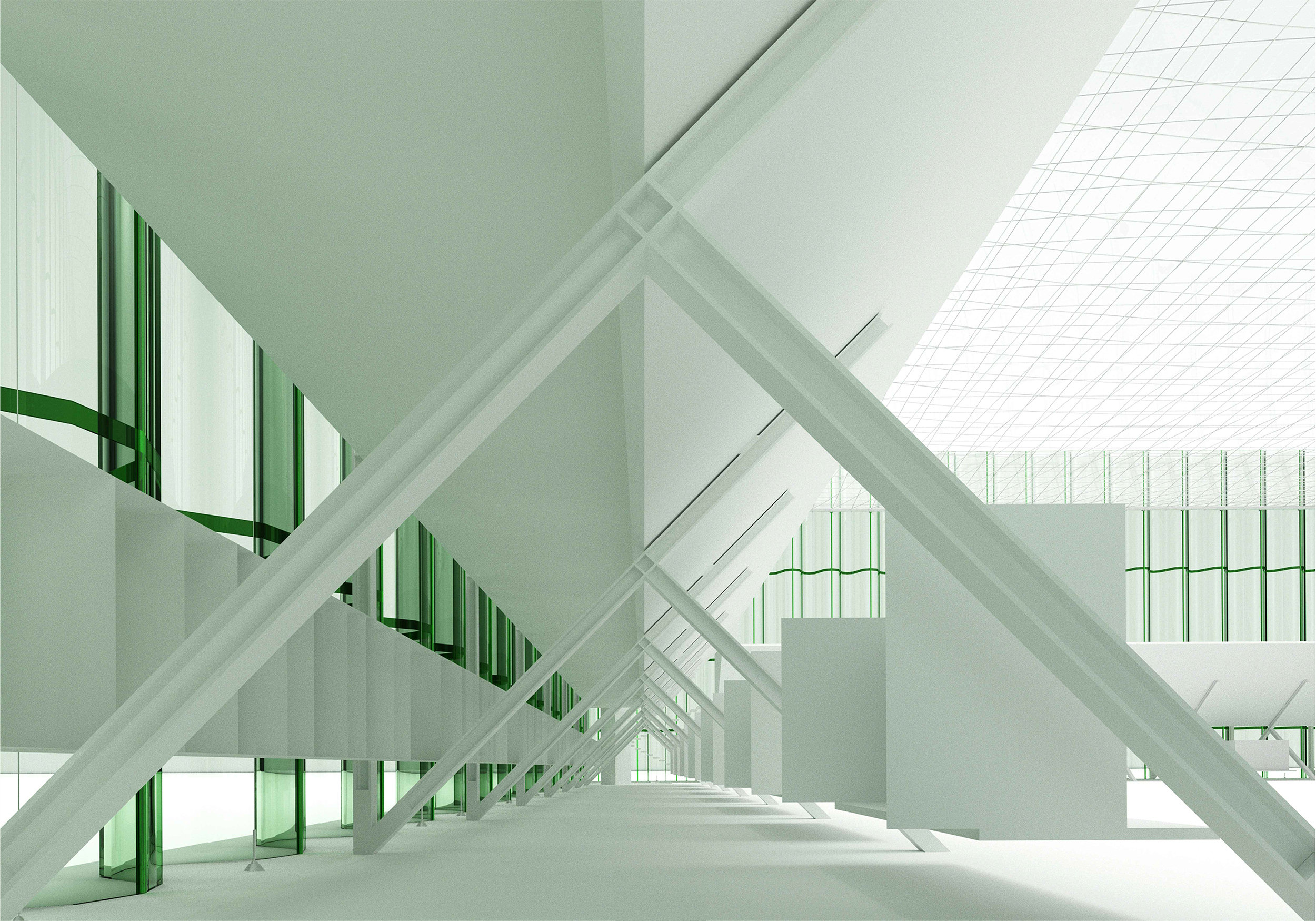

There are numerous examples of contemporary church architecture that does not adhere to traditions, yet provides much more potent spiritual experiences through their design. Photo credit: Keisuke Tanigawa

It’s all par for the course for an institution that is consistently fundraising for the poor despite never using the immense political pull it has to actually advocate for them (while never refraining from using it to stall societal progress) or its mythical net worth to support them itself. Traditionalism is perhaps more prevalent than ever because now it is also a matter of survival. This approach is consistent with the church’s role in the broader contemporary sociocultural context, too. It creates a haven of safety for people who see an ever-changing society slowly shifting away from their beliefs, morals, and values. Threatened by change, and apparently not realizing its inevitability, the Eastern Orthodox Church strives to preserve the status quo. And, through doing that uncritically, it seems to have missed the entire point along the way.

But hey, those newfangled chandeliers’ light sure does seem to cast a long shadow.

Short bio: Recently-graduated architect with an interest in photography. Secular humanist and consumer of media and information. I want to use my formal education and personal experience to give shape to our environment while trying to be conscious of the ways in which it, in turn, shapes us.