Author: Maša Čelebić

UM Faculty of Civil Engineering, Transportation Engineering and Architecture

One of the most significant architectural examples for the dead is Bogdanovic’s necropolis in Mostar, the Partisan’s cemetery. This city of the dead is a symbol of a child’s dream, innocent and endless in which the architect found his most significant work and succeeded to make a significant architectural work worthy of the last greeting of a man.

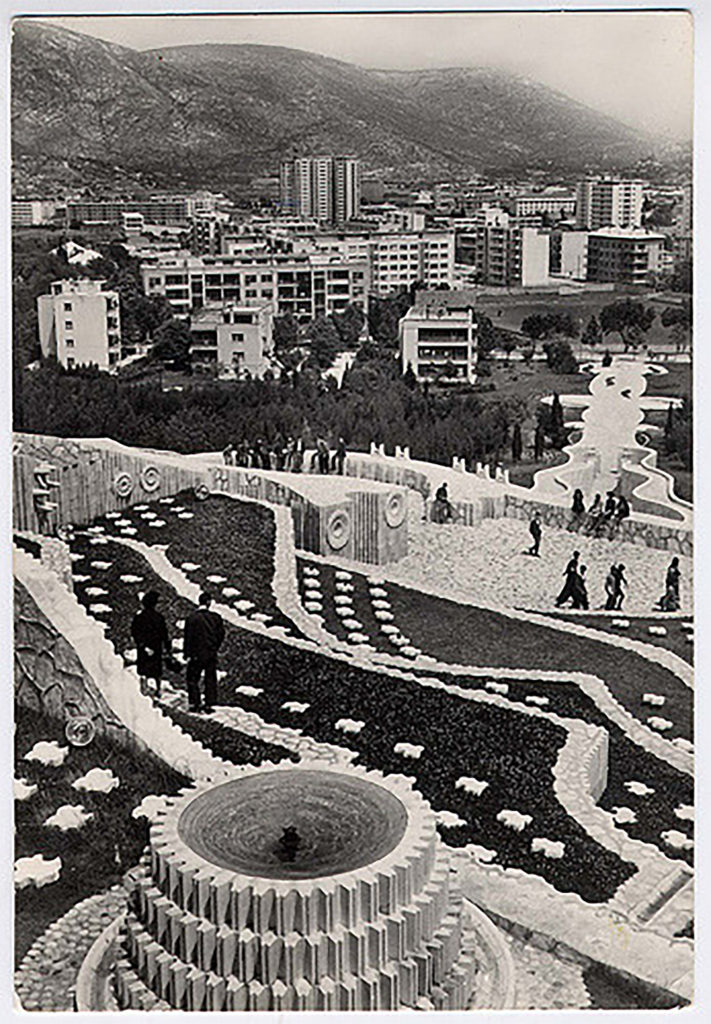

Bogdan Bogdanović was called in 1959 to design a memorial complex for the commemoration of 810 fallen World War II antifascists from Mostar on Bijeli Brijeg, south of the city’s southern outskirts. Bogdanović’s goal was to make a necropolis on the reputation of the old Etruscan sites in the Middle East (Niebyl, 2016). It represents the city of the dead, mirroring the city of the living, with the same cobbled paths, alleys, and gates, it is a microcosm of the city of Mostar (Mackic, 2015). Exactly how Bogdanović described: ‘two cities will look each other in the eyes: the city of the dead antifascist heroes, mostly young men and women – fighters and the city of the living, for which they gave their lives…’ (Bogdanović, Grad mojih prijatelja, 1997, p. 38). It was built slowly, laboriously and carefully, by voluntary contributions and also donations of stone from the fallen houses in the war, which gives it a special significance and symbolism.

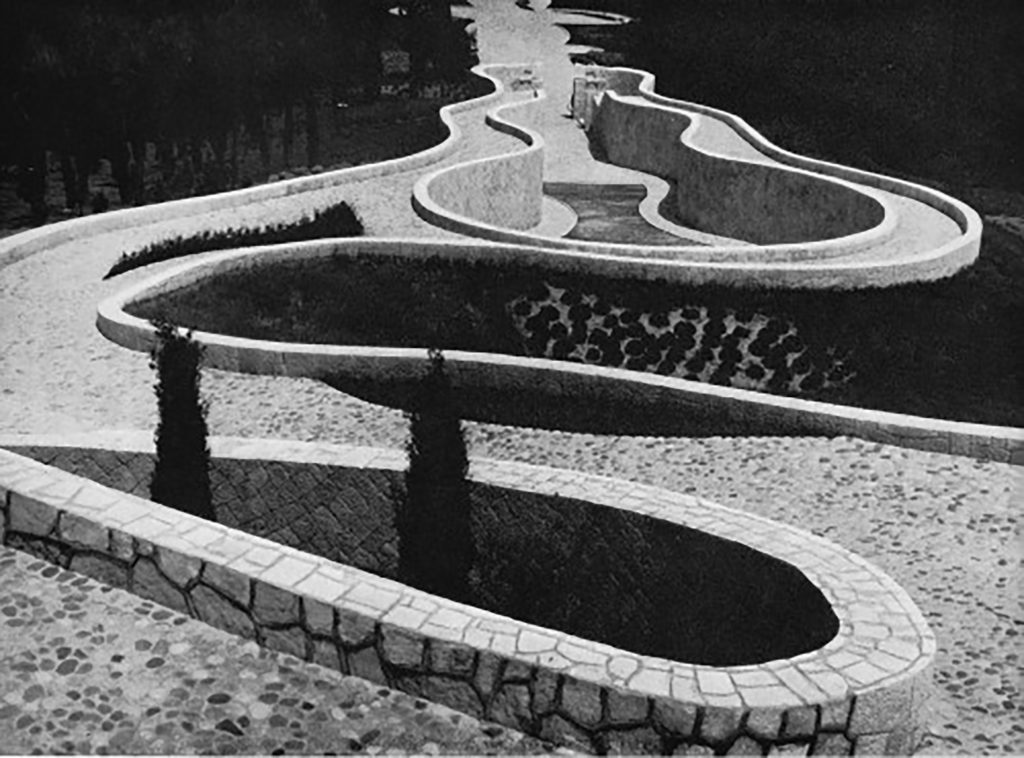

Partisan’s Memorial Cemetery, the path

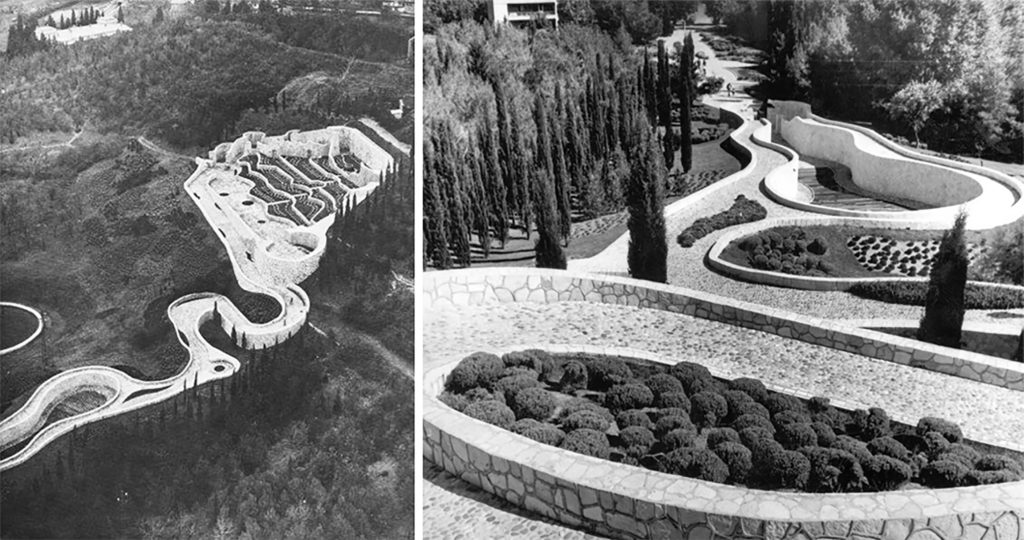

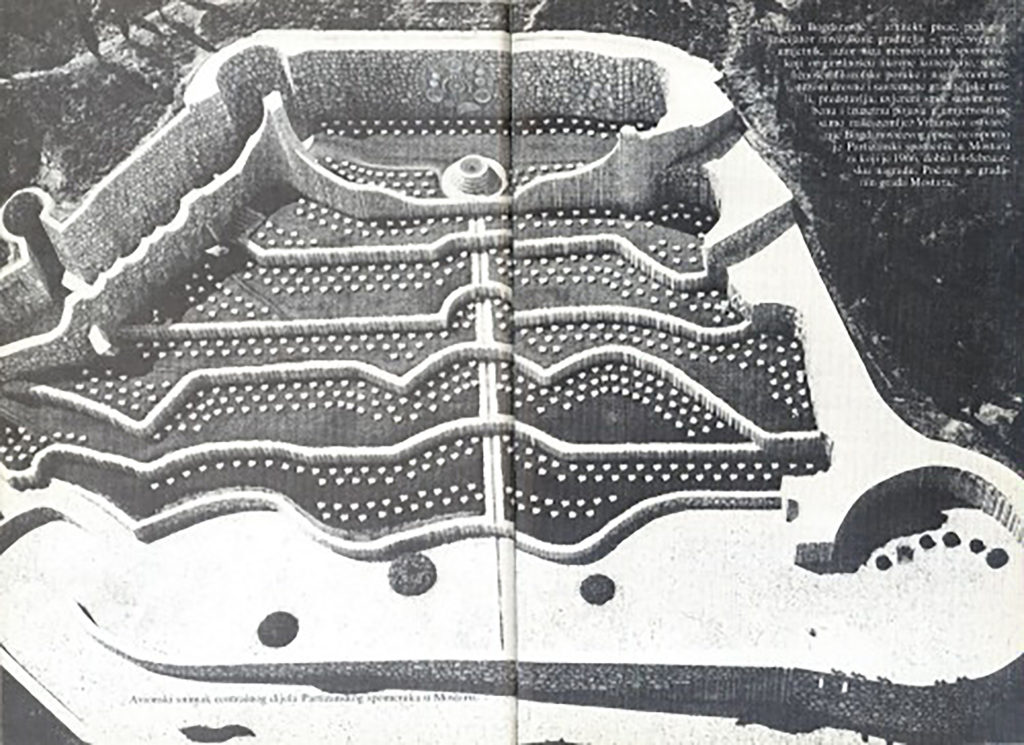

It was a big complex which had to ascend an elevation of about twenty meters. Using the stone from the Neretva River, a long curved cobble-stone walkway is the beginning that emulates the pats of Mostar by designing the walkway that is split into two parts with cascading water in the middle. The paths lead to the terraces that are built into the side of the hill. These terraces hold 630 abstractly-shaped stones markers engraved with the names of fallen antifascists. ‘Sources relate a variety of symbolic meanings behind these stone markers; firstly, some writings describe them as ‘bird-esque’ in resemblance, which is said to represent freedom and release from suffering- meanwhile, other sources describe the stones to be shaped similar to cut tree stumps, which would symbolize a disconnect and separation from youth. Yet, some propose that the stones appear to be of a flower-shaped design, which could be meant to represent the ‘blossoming’ of new life from the ground’, says Niebyl.

Monument stones on terraces

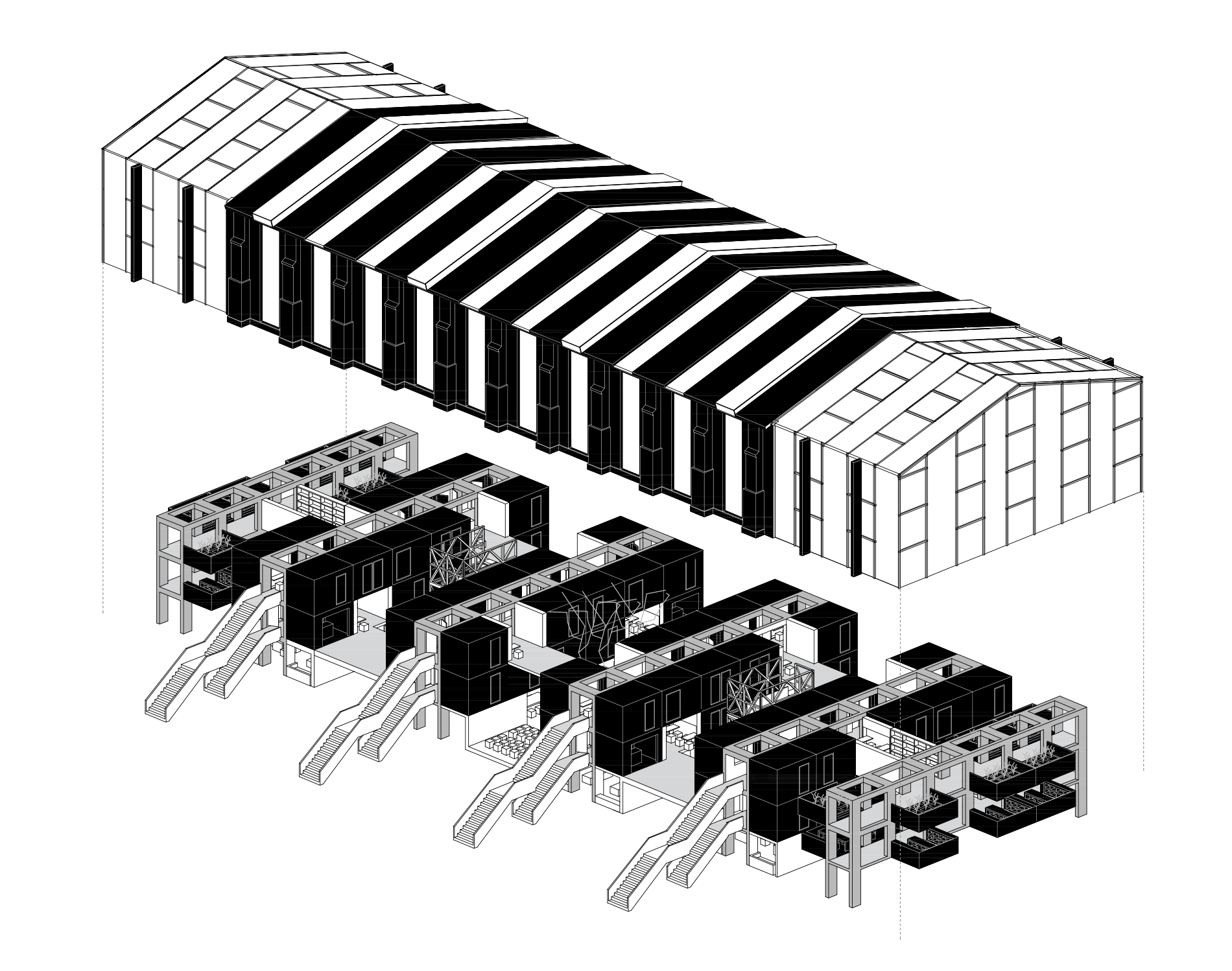

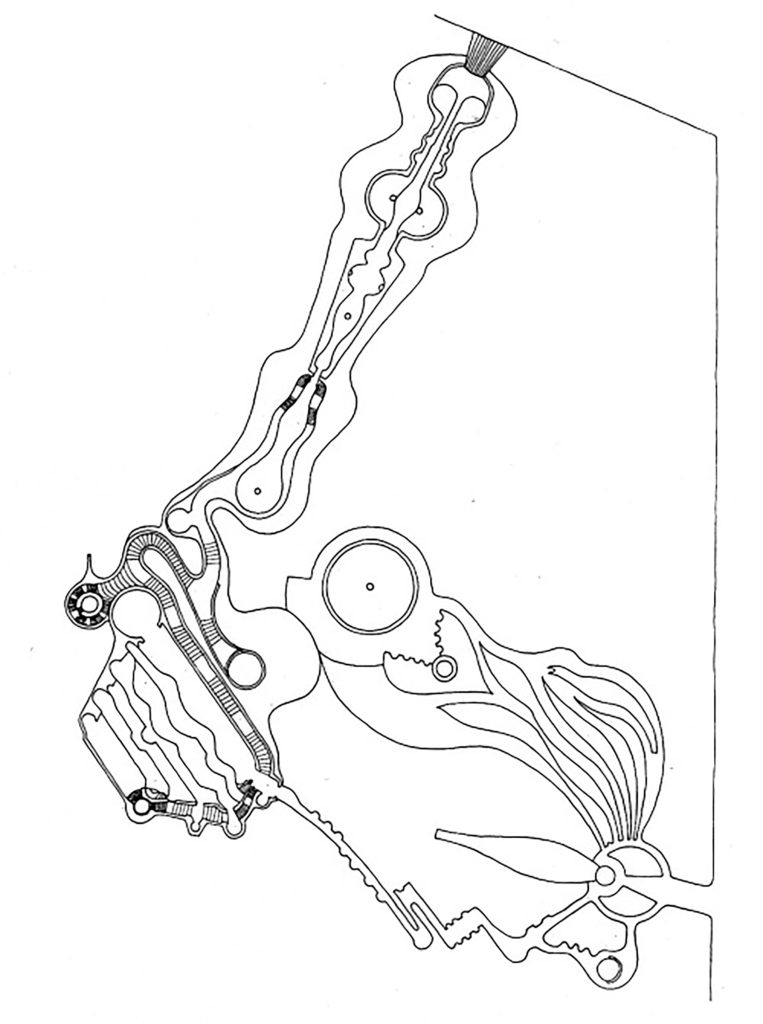

Plan of the cemetery

However, all these stones hold names of people with different religion and nationality, and yet there is no marking for that, which represent Yugoslavian unity and equality of everyone. At the middle of the top-most terrace, there is a large gear-shaped fountain which originally flowed straight down the terraces in a narrow groove, down the hillside where it collected into a large pool at the base of the hill. At the bottom of these terraces, there are three sculptures that show great resemblance to the Minoan ‘Horns of Consecration’, the secret bull, which represent the sanctity of the structure (Horns of Consecration, 2014). The primary focal element of these terraced sections of the memorial is a large ‘cosmological sundial’ design which is set into the wall at the very top of the memorial behind the gear-shaped fountain (Niebyl, 2016).

Cemetery, view from the top

Path to the cemetery

This is how Bogdanović describes this cemetery:

“On the highest terraces, at the inner stone walls of the “city”, in the folds of the stone walls: semi-circular niches, apse, buttresses — squandered themselves in hundreds and hundreds of stone flowers. At least partly because of the belief in the ancient suspicion of the builder-alchemist that the Mason is the child of the sun and the moon and that he, therefore, is so exceptionally suitable for, even destined to, the carving of heavenly phenomena, the stone flowers got abundantly mixed with the representation of the sun, the moon, planets, constellations … A place was found somewhere for the constellation of the Great Dog, which I had never been able to discern when I looked at the skies; and even for a group of stars that do not even exist in the celestial carpet, but that I christened “seven slender cows” in my imagination. For those not familiar with the question these were the Vlašići [referring to the Mountain Vlašići in Bosnia-Herzegovina]. Eventually, it turned out that the Partisan Necropolis as a whole recalled the grand astronomical model from which we all originate.”

(Bogdanović, Grad mojih prijatelja, 1997, p. 40)

The example of Partisan’s memorial cemetery shows what is the symbolism of the architecture for death. It communicates with the living, telling a story of life and death, making it attractive for people to come, to make that move easier, beautiful and monumental as it really is. It is a symbol of a dream for the eternal rest of men.

References

- Horns of Consecration. (2014, June 9). Retrieved February 7, 2019, from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horns_of_Consecration

- Bogdanović, B. (1997, maj/jun). Grad mojih prijatelja. pp. 37-40.

- Bogdanović, B. (2008). Tri ratne knjige. Novi Sad: Mediterran Publishing.

- Bogdanović, B. (2013, jun 23). Partizanska nekropola Mostar. Retrieved February 2, 2019, from nekropola tumblr: http://nekropola.tumblr.com/

- Lawler, A. (2013). The Partisans’ Cemetery in Mostar, Bosnia & Herzegovina: Leuven: RAYMOND LEMAIRE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION.

- Mackic, A. (2015, October 6). The Partisan Necropolis: Mostar’s Empty Stare. Retrieved February 6, 2019, from FA Failed Architecture: https://failedarchitecture.com/the-partisan-necropolis-mostars-empty-stare/

- Niebyl, D. (2016). Spomenik Database. Retrieved February 7, 2019, from Mostar: https://www.spomenikdatabase.org/mostar