From July 26th to August 11th about five hundred students from all over Europe met in Villars-sur-Ollon, Switzerland for the 2019 edition of EASA with the theme Tourist. The following is an extended interview with Saagar, tutor of SECONDSKIN workshop, conducted during the assembly for Umbrella.

U: SECONDSKIN is a workshop that blends many different principles but the end product is a multipurpose garment of quite a specific design. Is that something that was created during the preparation for EASA TOURIST?

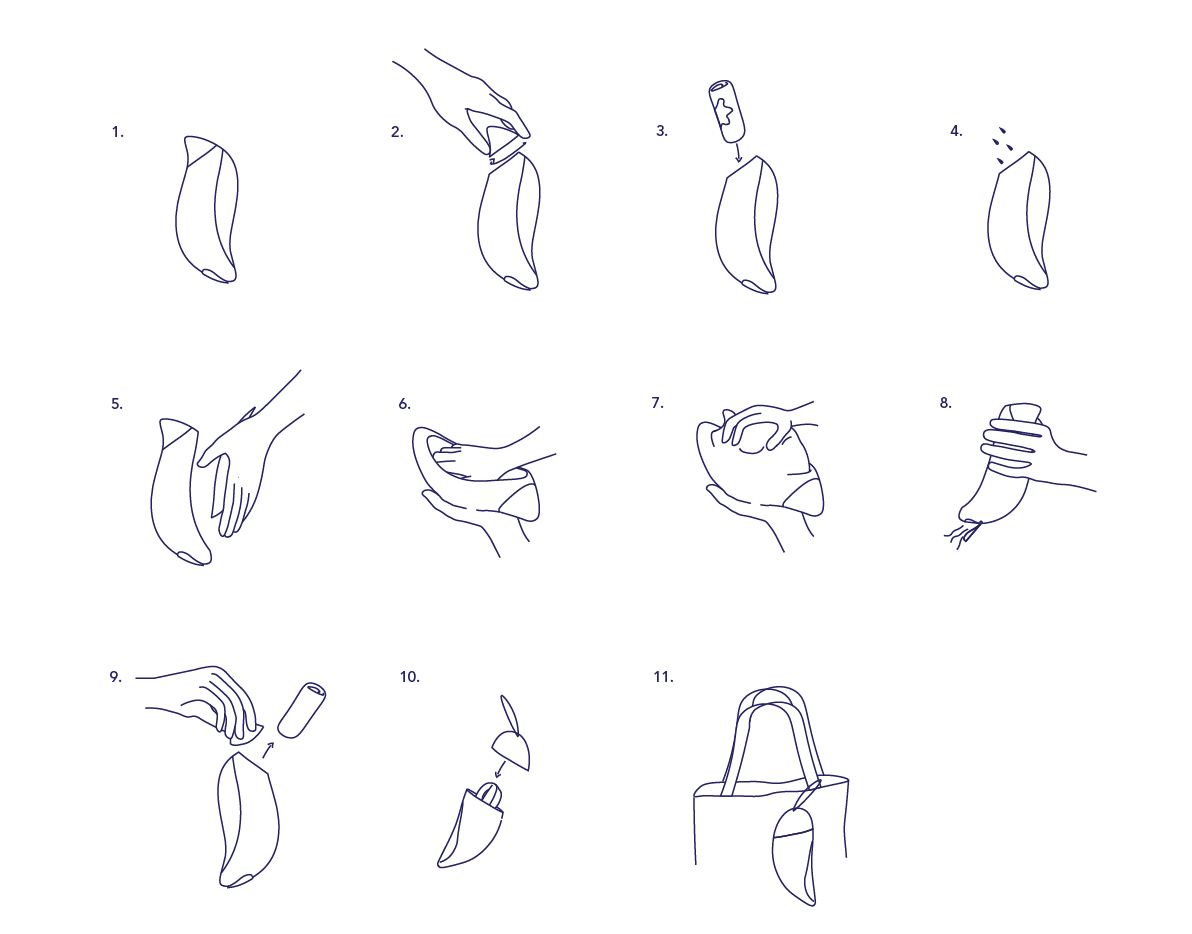

S: No, it wasn’t. The technique was developed before the assembly. Now, we are using the method to create the final objects, so the design is being done at EASA. The technique was developed by one of our co-tutors, a fashion and textile designer, to connect fabric and fabric together in a very simple way without using stitches, machinery, sewing, zippers… He calls it Button Masala. The idea was to take simple fabric to fabric joinery and apply it to the joinery of fabric to objects, fabric to structural elements, to create an intersection of textile design, product design and architectural design. We realized that when you mix all of these to create a simple joinery method you can create transformable objects which are multi-functional and can easily be made, not by the designer but the users themselves.

U: What was the motivation behind the project?

S: The first idea came when Shreyansh, my other co-tutor who is an architect, and I were discussing the project from the fact that we did not want to do construction. For the context of this EASA – the limitations force you to think light and simple. That led to us coming up with the idea of creating utilitarian clothing that you put on once and forget about it for a year. It takes care of you. That is where the name SECONDSKIN came from. So now you don’t have to worry about clothing again. After that a lot of discussion happened which made us realize that, more than just architecture and fashion design, it applies to groups like refugees and the homeless. If they have access to a system of design, they don’t have to purchase from the stores, or a product that doesn’t have to be distributed to them. If they can make it by themselves with the objects and material around them, you are supplying good design. The motivation is not to create this beautiful product but to replace the design of the user.

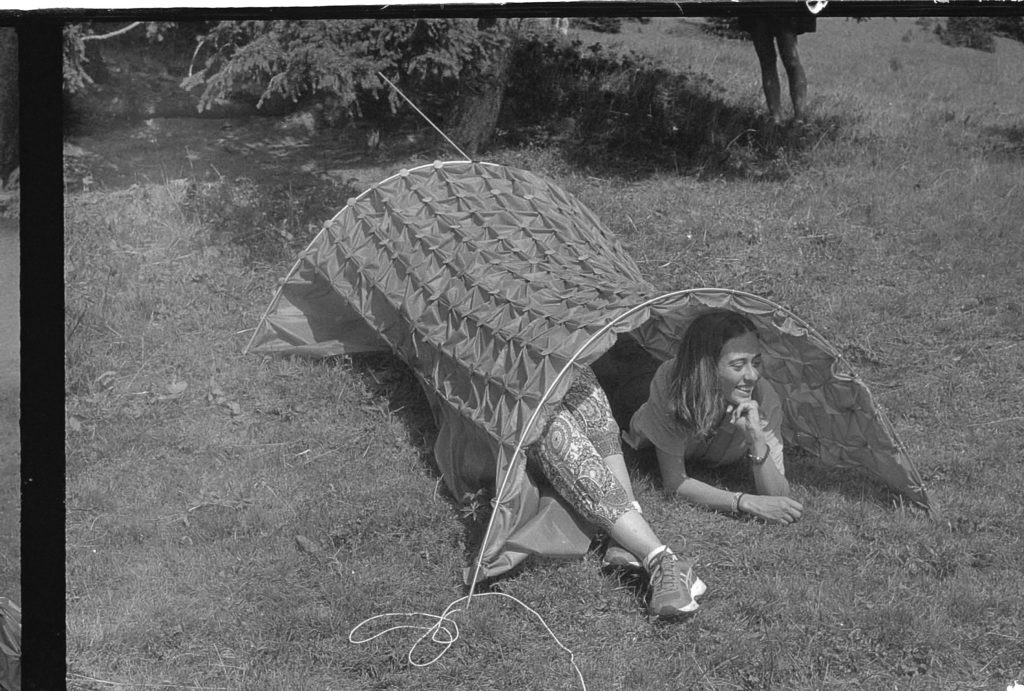

Soon we realized that we needed a textile fashion designer on board. That is how we met Anuj. He has this beautiful system that he uses for garment design. Our concepts and motivation and the journey all fit together perfectly. Together we tried to prototype a jacket that turns into a tent that turns into a storage system. And it worked really well which validated the idea that multiple functions are possible. What we are doing at EASA is just one palette of functions – jackets, sleeping bags, shelters, raincoats; because it supplies the context we are going to face after the Hannibal day, but a possibility of any number of functions is implied. The framework we are limiting ourselves to is that the journey and the concept remain simple and that you are allowed to create anything you want. But we are limiting ourselves to transforming wearable shelters, for now.

U: You talked about how you didn’t want to patent this design. How come?

S: The most important aspect of this project is that it is open-source and I think that is the only way to spread the idea. Another motivation is that people use it, build it and make it better. That is the only way for people to enjoy it more, use it more. If we patent it, it is always going to be this one specific product that needs to be distributed to people in need, or needs to be bought by them, which is not okay. Then it’s not going to be successful.

U: There is a lot of design specifically in response to the refugee issue. For example, Ikea has its own line of shelters. They are not actually gaining money from it but it is still a trademarked design. Do you see more open-source initiatives in the future?

S: The intention of these products is correct but the only way to give them out is for Ikea to make them and distribute them. Open-source design, on the other hand, can be picked up by anybody, developed by anybody and evolved by anybody. I think that’s what makes open-source beautiful.

U: I saw that some of your participants have tried to use bottle caps and such, so it really is flexible even in the material.

S: That is why we are focusing on the design framework and the methodology, which makes us completely independent of the material used.

U: Yet, you are using one fabric at the moment.

S: Correct. Again, for this context, because we have to camp during mounting, we are using two types of fabric. One is a weatherproof fabric, super light, which we are using as the outer layer. The second fabric is a slightly thicker weatherproof fabric that we are using for putting on the ground. We are trying to limit ourselves to these two, but again the idea is that any material can be used.

U: In the future, how do you plan on distributing the design idea?

S: The easiest way to do it is through publication on the Internet so we want to make sure we document it really well – DIY videos, papers on the importance of open-source and why this is a good example of that – so that people see that something like this is possible. Even if somebody is looking at a poster, watching a video and they do it themselves, than that’s enough. I also believe that good design spreads by itself, especially when it’s open-source and we are hoping that drives the design forward.

As of now, we started an Instagram account @secondskin.project. We are trying to upload everything there for now, but once we collect all of this data, all the documentation, we will figure out the best and way of publishing it. We will talk to magazines, of course. I think that is one way to propagate the design within the design community but obviously this has to go beyond that. It can’t be just published in the design community because that is easy. We want to push it outside. We have to figure out how to interact more with the regular media rather than just the design media.

U: How do you feel about your workshop in progress?

S: Great. We have some beautiful participants. They are really creative, which is very important because there is no set design so it takes a bit of extra effort from the participants to figure out what they want to do. We did this exercise where we asked the participants to define the user, their problem statement, and then define their design brief. For example, this girl from Serbia has defined the user as a young Roma mother who is homeless and needs a waterproof shelter and a baby port. So, now she is designing a wearable raincoat that also has a baby port inside of it and it converts to a tent, which is amazing. Another guy from Cyprus, who’s defined the user as a hiker at high altitudes, is designing a high-altitude multi-function jacket that can store a lot of things. The idea is to make a quick shelter out of it.

U: And the bicycle tent? Is that still a thing?

S: Yes, yes. She actually got a bicycle and she is trying to figure out how to create her tent from it and maybe add more functions like a bicycle cover and things like that. Another girl from Turkey, whose users are refugees who are running away from economic crises, war zones, etc., is creating a life-jacket from thrown away bottles which, again, can turn into a shelter.

U: The more workshops you do you will probably reach out to even more creative people who will think of new uses.

S: And the best part is that you don’t have to do workshops. People can just pick up the idea and start creating.

Film photographs by Boris Stanković.