Parsa Kamehkhosh (b.1985) is an Iranian artist based in Helsinki, Finland. Being in the world is all he is trying to experience. Being present with all of his senses and letting himself be touched and fascinated by what life puts forward. He is constantly internalizing his perceptions and reflects on them in the form of “bringing things”. This natural process is actually a way towards understanding his position in the world and expressing his appreciation of it. The outcome usually works either like a mirror that reflects untreated or unrevealed aspects of his personality or a practice through which he encounters and contends with his inner tensions. He believes more in bringing than creating because he identifies himself only as a door through which idea can enter the conceivable realm of existence in a certain way.

His latest piece is currently on display in OBJEKTI which is an outdoor exhibition of contemporary sculpture, installation and environmental art in and around Espoon keskus, Finland 14.6.-2.9.2018. The piece is a series of nine object-oriented performances, through which he will be lying inside a metal cube and sculpting it from inside. His actions and movements inside the cube will affect the exterior of the metal piece and change it gradually.

There are still two performances coming up which will take place :

25.8.2018 at 18:00-19:00 (Espoo Day)

2.9.2018 at 17:00-18:00 (exhibition closing day)

If you find yourself in Finland this summer, stop by and visit this piece located next to the pond of Kirkkojärvi in Espoon keskus.

Follow Parsa Kamehkhosh on Instagram to see the latest updates on this piece and see the performances live.

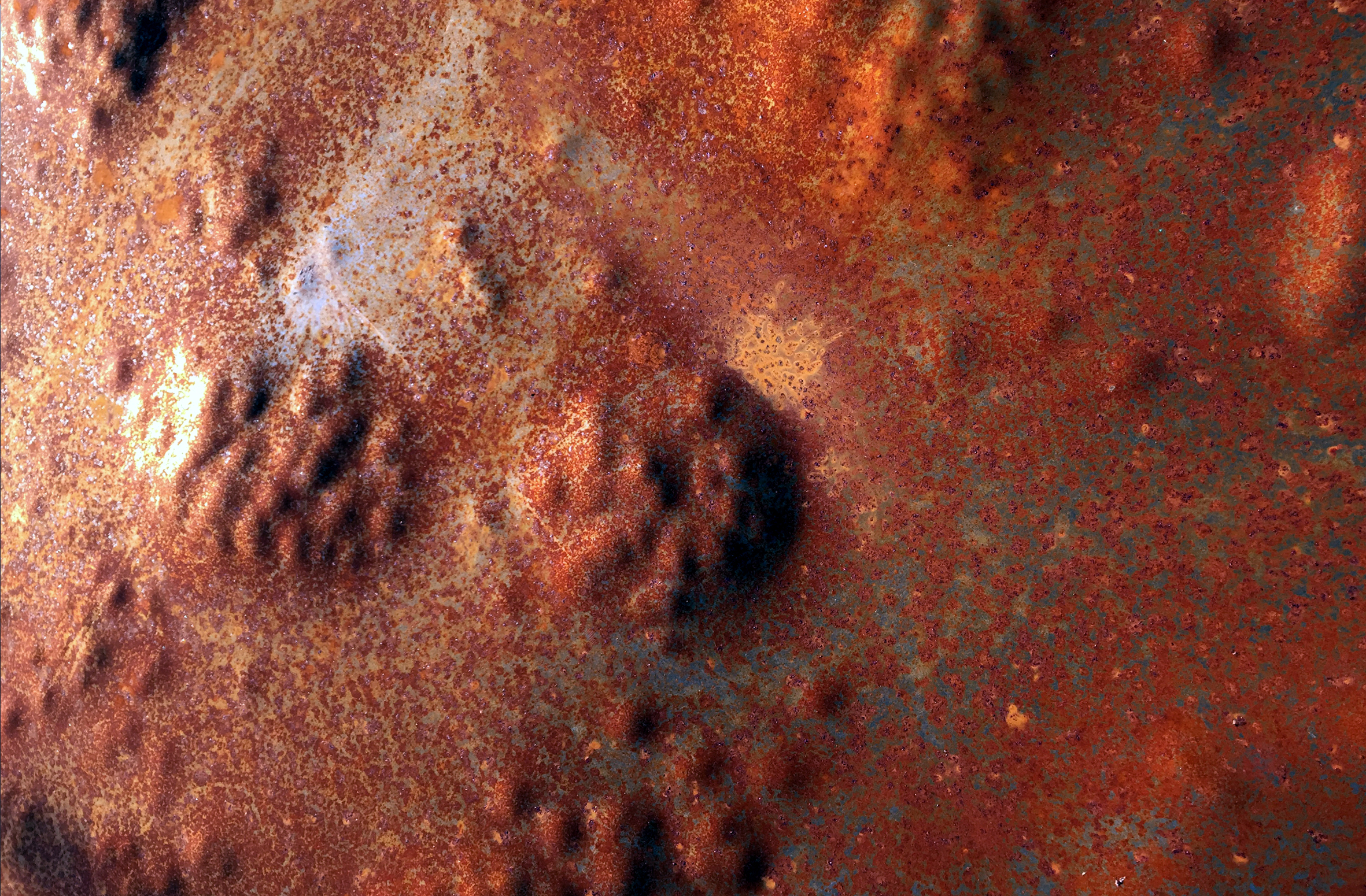

Indeed an object. A metal box placed on wooden logs, it presents itself with colours, textures, structure and proportions.

Its simplicity allows for focus on its detail. The colour of the metallic surface so dependent on the light, fluctuating like the surface of the water, partly dark, partly reflective. The rusty patches on the porous metal, the apparently solid material undergoing decay. The wooden logs have a gap between them, making the whole thing look more light and airy, as if it didn’t need solid support. Its body cuts itself out from its surroundings; it is clearly man made, yet neither its placement nor any other visible signs betray its purpose.

The welding marks are spread irregularly and each has a unique shape. They owe their colour to qualities of material and their shape to the technique. They are a record of heat affecting the material. Wooden logs have lines marking the yearly growth of the tree, bark and darker parts of gnarl where branches grew. Both the box and the logs speak of decisions the artist has made, and of their own history and qualities. This happens thanks to them being in their raw state.

The artist doesn’t control every detail but rather works with the material. The material has its own agency.

In Parsa’s work, the organic and the man made are brought to the same plane. These materials are coming from the environment, and they are subjected, like all matter, to constant change. He does not use a chrome surface or a crystal vase, materials that can give an impression of being uniform, impenetrable and unchanging. The material used tells where it is coming from and reveals some of its qualities and its history. It seems to be there not only as a vehicle for something, but also for itself. We have our own form and we are surrounded by forms. This work can make us look and consider what form is in and of itself.

This whole process could be hidden in that single observation: the exhilaration at the sight of an autumn leaf, its palette and gradation of colours, can correspond with exhilaration felt at the sight of patches of rust on the metal surface, shapes and colours they appear in.

Rust – oxygen reacting with metal, another process in a form that is undergoing change. The erosion of this solid material shows the constant change of matter. All things come to be, and fall apart, a journey of matter through forms.

[FinalTilesGallery id=’13’]

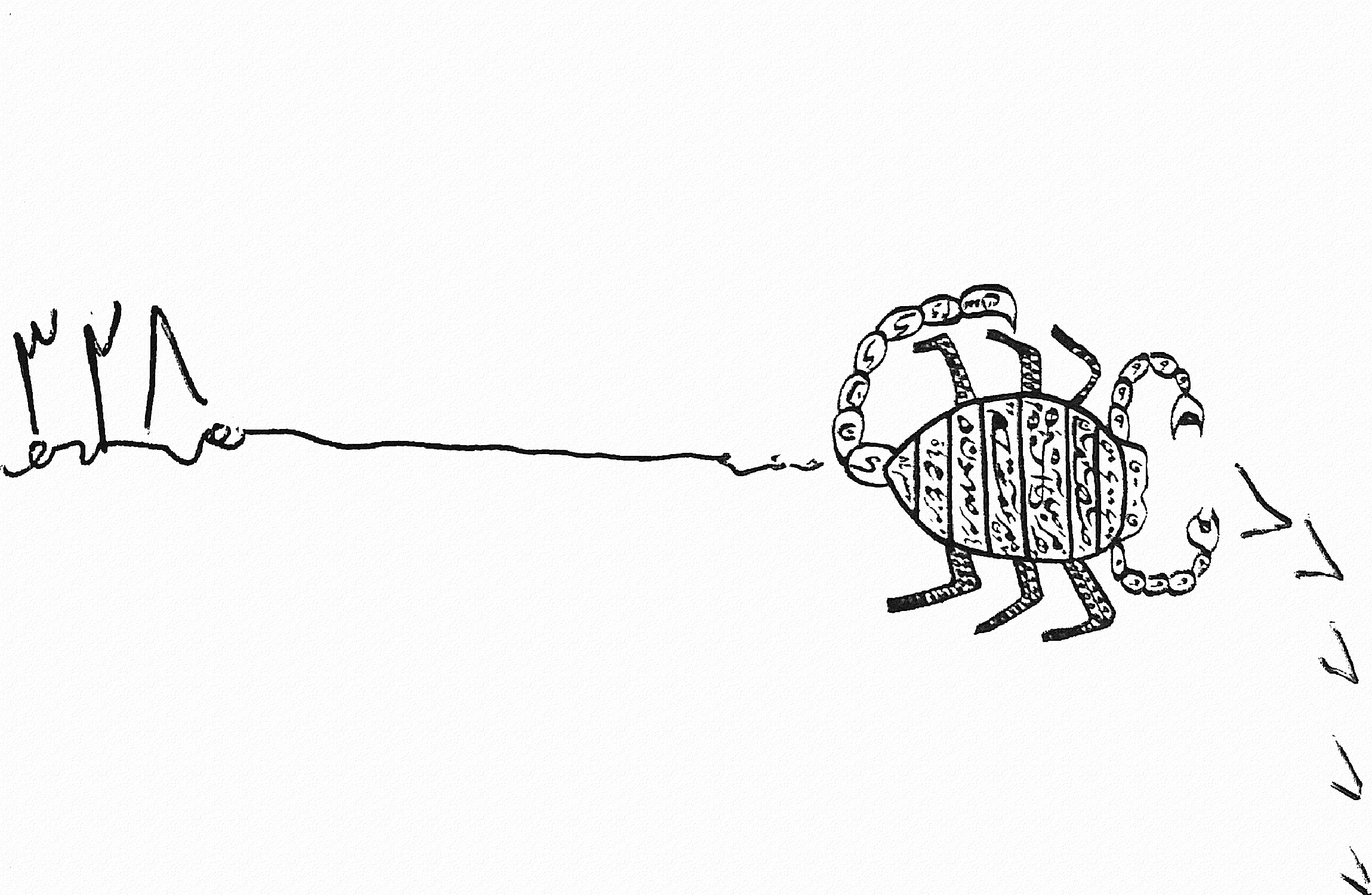

Parsa performs an act during the exhibition, sculpting the metal box from within. The hard surface changes form in front of our eyes. With the noise that it makes, this intense situation points to the artist’s determination and the state of mind that brought this to be. In relation to us and to the matter it speaks of our capability to shape our surroundings. How we choose to act in our environment depends on the shape of our consciousness, therefore our responsibility for the shape of our consciousness comes to the front. And a part of this is perhaps paying attention to what’s around us in the first place.

The artist is clearly present but remains invisible, manifesting himself through material and contact with it. Consciousness and material are one, consciousness shaping surroundings, and vice versa. The weight of Parsa’s gesture as I see it is in materializing this idea.

The piece is also a sculptor at work. This inclusion of an organised action that requires certain effort points towards consciousness, our surroundings and existence of them both as a process rather than anything that can be pinpointed at any given point as this and not anything else. Conscious work or not, needing more effort or less, it is not an instant matter but a road with no point of arrival.

The shapes that come out through this act share characteristics with organic matter – they are round and bulging like a parasite on a tree, they are irregular and scattered. This emerging form can send our thoughts to the organic source of all materials, an endless abundance of forms, and our relation to it.

This situation can be contained in a single event of marvelling at the shape of a mango stone, and taking in the full impact of this event. It is not about momentary amazement at the setting sun, replaced immediately when we turn away by other fleeting thoughts. It is about lasting feeling, an attitude, a way of connecting to our surroundings, a presence. It is perhaps a reminder of some raw qualities of the world we live in, and the fundamental ways that we engage with it.

Written by: Jakub Bobrowski

Edited by: Laura Jarvey