Redefining the concept of neighborhoods in contemporary cities.

author: Sotiris Frankos, Athens, Greece

As an architect, I have developed a particular interest in the design of homes, with both my diploma design project and my research thesis concerning community housing. Clarifying why I thought a community should be placed and developed inside a building as opposed to public space was fundamental. In the following text, I shall present my thought process in a concise and hopefully convincing manner.

“What should young people do with their lives today? Many things, obviously. But the most daring thing is to create stable communities in which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured. “, Kurt Vonnegut

The Erosion of Social Space and Life in Contemporary Urban Centers

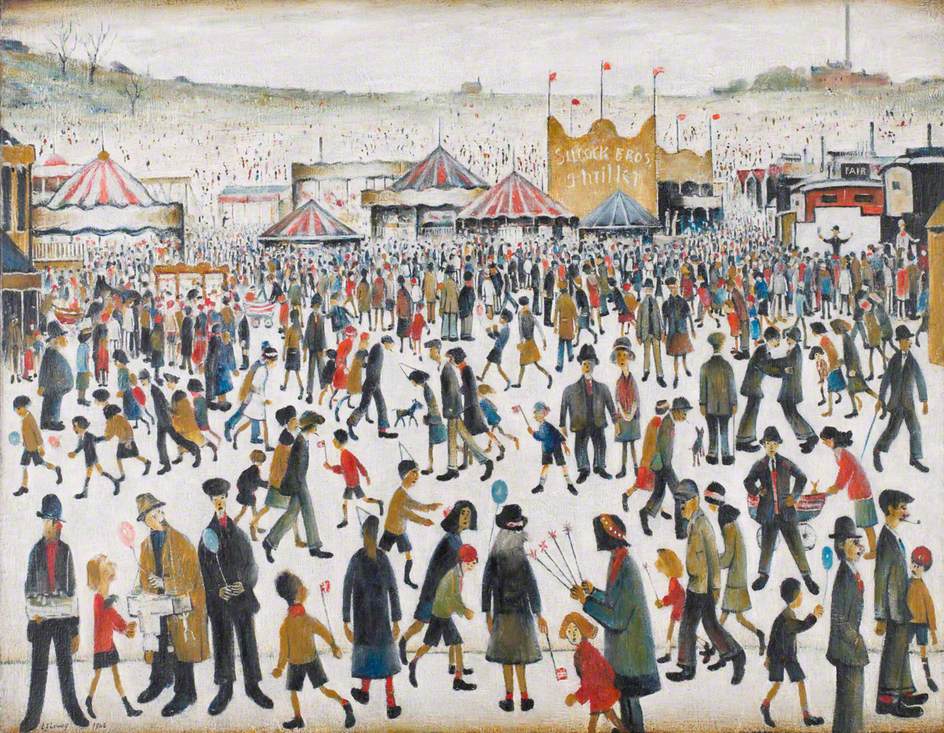

Referring directly to post-war urban living, distinguished French philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre recognized its consequences in the feeling of community it seemed to be having. He referred to “moments” in daily life that revealed the way to a better future society, moments such as big celebrations in which communities would come together. Those moments cannot but constitute simple breaks in contemporary everyday life, and there can be no fundamental changes in it without fundamental changes in the space it takes place in. Lefebvre’s point of view seems to be in full agreement with contemporary theories concerning the consequences of today’s urban environment that connect it with significantly increased rates of loneliness, social isolation and mental illness.

With contemporary life revolving ever more around the home, especially with emerging trends such as working from home, finding an answer to the problems the post-war built environment introduced should be a priority. With the importance of social interaction for an individual’s health and well-being being paramount, and directly associated with loneliness and social isolation, it would make sense to try and tackle the aforementioned problems through focusing on attempts to increase it in an urban dweller’s daily life. Social isolation, however, in a contemporary urban context is not an issue that emerged as a result of changes in the space of the home itself but by changes to the extended residential environment, and the possibility of neutralizing some of these factors, or at the very least attempting to restore them to their previous state in the pre-war urban environment, is not a realistic one. Equally unrealistic is primitively attempting to return to earlier living conditions, an approach one can entertain when treating the past nostalgically. For example, the concept of neighborhood in the contemporary urban environment cannot exist in the same way it does in the rural one, or in urban centers of the past. Only through critically reapproaching these concepts and conditions does finding solutions for today become possible.

Since the publication of Georg Simmel’s incredibly influential “The Metropolis and Mental Life” over a century ago until today, concerns for urban social interactions have largely focused on the fact that they occur multiple times a day but ultimately not enough to satisfy an individual’s social needs due to their lack in quality and due to the urban individual’s suspicious predisposition to strangers in the urban environment, which is often described as unsafe, particularly in comparison to residential environments of the past.

In addition, the decay of already existing open, collective spaces is accused of eroding the feeling of “home”. More specifically, in the past, city dwellers would appropriate public spaces surrounding their residence in a spontaneous manner as part of their participation in public life. Eventually, and starting with the 18th century’s gradual separation of home and workplace, a series of changes affected the relation of houses to urban politics, social life and space. Intermediary spaces independent of state influence disappeared gradually and every facet of urban life came under state control and surveillance, with communal spaces starting to be dependent on it as well. The consequences of this shift can be found in innumerable facets of collective and urban life, with activities taking place in those spaces being controlled and as a result limited to a set of allowed activities based on written and unwritten social rules.

An Attempt to Restore Social Space in Contemporary Urban Centers

There have been a number of movements focusing, at least in part, to attempts to restore those qualities to urban space. A relatively recent one is new urbanism, which defines its aim as the creation of active, sustainable communities through a series of design guidelines, with the end goal of raising the residents’ quality of life. Reapproaching the traditional neighborhood structure is of particular importance, through the definition of a clear center in each area with quality public space and multiple different services being provided. With high-density housing the goal is for every able-bodied resident to be able to access the aforementioned center and all its services on foot within 10 minutes from their house. In general, pedestrian accessibility of the urban fabric is a priority. Deemed of equal importance is environmental sustainability. The movement promises a long list of benefits to the residents of such an urban environment, among them being the formation of a friendly community as a result of the increased possibilities for social interaction with other residents. It should be noted at this point that, even though new urbanism is concerned directly to urban design for the most part, its guidelines and philosophy indicate the possibility to be applied to design of any scale, including the design of buildings.

The new urbanism movement, along with other similar contemporary approaches to urban design, seeks to facilitate the quantitative increase of social interaction, but have often been accused of being unable to guarantee qualitative adequacy through the creation of substantial relationships, which are nevertheless of equal importance for the reduction of loneliness and social isolation.

One of the most basic needs a home responds to is the feeling of safety its space provides to its residents. It is through the known and the familiar, in stark contrast with the unknown and unfamiliar of the urban environment, that extends it beyond its physical boundary. It is a place in which the resident has a sense of control, power and autonomy that is not present outside of it.

Through this lens, the space of one’s residence provides an appropriate background for the development of substantial human relationships. The home typologies of contemporary cities, however, were not designed to serve this purpose. Indeed, as social spaces the houses of today are relatively limited. The residence is usually a strictly private space, with transitional spaces between it and the urban public space being relegated to mostly spaces for movement. Therefore, contemporary homes are unable to be used as spaces in which new social relationships can be developed. Furthermore, they do not respond to large social gatherings adequately, which becomes quickly evident in activities like birthday parties.

It would be ideal then, to create an environment within the context of a home that does not restrict the resident’s social life but attempts to answer the aforementioned problems through reapproaching concepts and restoring qualities lost in the contemporary urban environment.

A Community Inside the House

References have already been made to the feeling of safety in a home and the erosion of collective spaces in the urban environment. A thought that emerges from that analysis is the creation of those intermediary spaces, outside the reach and control of the state and the danger and suspiciousness of the urban environment, within the framework of the house. Clearly, the creation of common social spaces in the context of a house directly alludes to some form of cohabitation.

Transitional spaces, as mentioned above, in today’s dominant urban housing typologies, usually are relegated to spaces solely for movement. Since they are not vital spaces there is no incentive to explore their potential by neither developers nor clients. In spatial arrangements that facilitate cohabitation, however, the spaces between the completely private of the residence and the completely public of the city acquire considerably more meaning. The dichotomy of concepts such as private and public, inside and outside, that largely dominate the housing production, already seems to be deconstructed in contemporary architecture. The non-binary treatment of these concepts is not an exclusive advantage of cohabitative architecture – but precisely because of the elevated role of transitional spaces in its context, it constitutes particularly fertile ground for experimentation and the creation of new typologies through it. The deconstruction of the private/public binary is a prerequisite for the existence of any sort of architecture of this type.

A term that can be used to describe the condition inside this form of housing (or at least the one it would attempt to create) is micro-neighborhood. According to Donald I. Warren:

The micro-neighborhood is operationally defined as the next-door neighborhood, the person in the next apartment, or the most immediate set of adjacent households. It is defined when a mother yells out the window to young people playing in the street, “go play in your own neighborhood.” That notion in turn leads us quickly into the notion of the residential block.

Cohabitation is then able to provide a contemporary approach to the concept of neighborhood in the context of the urban residential environment. However, this neighborhood is not necessarily confined by the boundaries of the building it is developed in. In fact, an individual’s activity in matters concerning that community increases as well the possibility of them taking part in similar happenings in broader communities (such as the residential block, or the city), nurturing the sense of belonging to a larger whole. Specific proposals, in fact, through the design of mixed-use complexes, attempt to actively encourage the development of an extended community. It becomes apparent that different decisions concerning the design, structure and multiple other characteristics of the building can greatly affect the micro-neighborhood. But that’s outside the scope of this article, and by this point, you will ideally be interested in looking into it yourself.

Short bio: Recently-graduated architect with an interest in photography. Secular humanist and consumer of media and information. I want to use my formal education and personal experience to give shape to our environment while trying to be conscious of the ways in which it, in turn, shapes us.