Before commencing the discussion on the relationship between Modernism and Modernity, we should in brief look at the nature of the approach we are inevitably going to take. Namely, the fact that cultural criticism has its deepest roots in the tradition of Marxist criticism is often kept in the background. Therefore, we shall immediately introduce the fundamental critical concept we rely on, and its origin in the Marxist criticism. Raymond Williams attempted to explain the concept of historical conditionality of cultural phenomena (albeit primarily of literary texts) through his concept of cultural materialism. Here, the materialist notion primarily points at any cultural phenomenon being unavoidably rooted in the political, economic, or better still, ideological situation in which the work is created.

Taking up such an approach may seem contentious from the postmodern perspective which proclaimed a vision of our times as postideological. Not wishing to tackle this issue, we shall simply emphasize the fact that Modernism, which is dealt with here, was the period of the most powerful development of ideologies as well as of their theoretical (or as Marx insisted: scientific) elaboration.

*

It is necessary to differentiate between the two notions. Modernity appears as a kind of relationship towards reality, a state of mind, both on the individual plan as well as on the collective one. The concept of Modernity as it was at the end of the Middle Ages changed with each new successive historical period: from the Renaissance, through Enlightment, Romanticism, up to the period of Modernism, while today we are following the postmodernist redefinition of the concept of Modernity. The very idea of successiveness and changeability of tendencies, i.e. periods one after the other, is modern⑴ on its own. On the other hand, Modernism can be defined as a more or less coherent ideological position and (not only cultural) practices generated from it, which are, nevertheless, conditioned by the modern state of mind as well as by the given conditions in a certain historical time in which Modernism exists. Indeed, Modernism is a tendency within which all features of modern views of reality are interpreted and applied on most areas of every-day human practice. Therefore, attempt should be made to define the characteristics of Modernity, and also to define the characteristics of Modernism related to them, in order to conclude what and how modern theory and practice have acquired from the accumulated heritage of Modernity.

The differentiation made here is in a similar way present in the works of Romanian theoretician Matei Calinescu. In his treatises he always sets off from the presupposition that there are two distinctive types of modernity: civilizational and aesthetic. The civilizational type starts, in the widest sense, with the domination of the Christian concept of time, while later its foundation becomes the doctrine of progress. Aesthetic modernity, on the other hand, begins as late as the mid-19th century, predominantly with the Charles Baudelaire’s⑵ aesthetic concept. At this point we shall skip the commonly known discoveries⑶ in the field of humanities and exact sciences which have, since the Renaissance up to the present, made the nature of Modernity change. Following Calinescu’s line of thought, we would like to point out that the beginning of the domination of Christianity led to the first crucial precondition of Modernity as early as at the end of the Antique period – it was a linear concept of time which flows successively. Furthermore, the breakthrough of Antique ideals during Humanism presents itself in Petrarch’s awareness of a disruption in the flow of history, specifically a break between the darkness of the Middle Ages and a new era in the future, which is supposed to be turned into a bright era by the Renaissance homo faber with his own willful action. The revolutionary quality, therefore, lies within the abandonment of the medieval vision of continuity of time flow and the realized possibility of the occurrence of novelties (but independent of manifestations of transcendental powers). Apart from the optimism regarding the great industrial progress of the time, the Enlightment tendencies also bring about some heated debates between the old and the new in the field of arts, out of which the transcendental character of the notion of beauty does not essentially change (Calinescu: 42), but independent of those debates Kant’s philosophy brews ideas which anticipate the autonomy of art. Beauty becomes a historical and non-transcendental category only with Stendhal, who speaks for literature that would deal with current reality. At this point we stand at a protomodernist position where it is imperative (and even aesthetic) to show awareness of modern life. Furthermore, Baudelaire brings about the well-known breakthrough in perception whereby every past period had, in fact, its Modernity, just as Baudelaire’s time has its own Modernity; therefore a writer has no inspiration in tradition (since it is not his current time) but he is left only to the imagination – a power of searching for the new. This, in fact, makes Modernism itself a constant reexamination of all potential (new) modes of Modernity (Calinescu: 71), it is a reconsideration and search of Modernity and the continuously arising new current realities. Thus arising from the whole heritage of Modernity, Modernism became ready to get even with itself (as an emerging tradition) and during reexamination even to counter the terms which are fundamentally immanent (rationality, progress). Its symbolic pinnacle is definitely the Dada Manifesto.

Attempting to explain the notion of Modernity, Lefebvre, on the other hand, insists on the contradiction of Marx’s and Baudelaire’s understanding of nature and reality.⑷ He also holds the opinion that the key twist in discarding the idea of the continuity of reality happened after atomism and structuralism explained reality in a different way than evolutionism, and not in the transition between the Middle Ages and Humanism. Attempting to make a dialectic analysis of Modernity, he gives contradictions such as: atomization (individualism) – totalization (repression of a totalitarian society), security – terror, desire⑸ – new moralism (communist utopia), which demonstrates the specificity of a current Modernity. He explains it by saying that “the instant is no longer the shifting reflection of a distant eternity, but the very threshold of the eternal” (Lefebvre: 184). Problematizing of Modernity as we see it today also leads us to Habermas. In a dispute with the neoconservatives – their views on the moral foundations of purposeful living or their postmodern alternatives to instrumental mind – Habermas attempts to build an apology of Modernism⑹, which was so fervently attacked by the same neoconservatives in the past decades. Habermas builds this apology on the belief that Modernism can connect the presently so differentiated fields of science, morale and art, and to protect any form of communication (discourse) from the imperative of the system. The Enlightenment idea that objectivizing science, universal morality and autonomous art can together serve “the intellectual shaping of life relationships” (Habermas 1983: 9) failed in the 20th century⑺ due to the full autonomization of art, among others. It is in the avant-garde when this fragile autonomy was most radically attempted to be annulled, but according to Habermas certain mistakes were also made – it was not enough to simply merge art with every-day life (annul expert discourse and differentiated expert cultures), it should have also been done with the sphere of morale and science; similarly, breaking art as an institution and structure within which there existed a code for producing meaning of artworks, did not yield any constructive result. As alternatives that could return Modernity to the objectives drawn up by enlighteners, Habermas presents the idea of “explorative aesthetic experience”⑻ (Habermas 1983: 14) as well as the necessity of the non-capitalist quality of the further process of modernization. Therefore, Habermas is at this point, a thought-provoking author since he sees Modernism as a not definitely closed whole, and which could live on, following its earlier heritage, parallel with the postmodern tendencies which negate it.

Seen as a whole, on the level of philosophical discourse, moderns set off by discarding the materialism of the 19th century, positivism and scientific determinism, but also discarding faith in the “ontological grounds of human nature on the idea of continuity” (Everdell: 6) which is the foundation of every single thing. Such an image of the world falls with the ascent of the atomistic image that destroys this determinist dynamics. All this, initially in the field of art, is the source of distrust in formal logics opposed to which the idea of ‘self-reference’ is founded, i.e. an idea of a world which is “nonlogical, nonobjective and causeless” (Everdell: 10). It is in the same way that postmodern thought subsequently tended to problematize ideas set up by moderns: a concept of a powerful subject (that can create and master philosophic systems), an idea of metanaration through which objectives of human actions are legitimized, an idea of the principle of wholeness, as well as a modernist concept of identity which is related to the criticism of the Cartesian subject able to subdue the world to himself. The simplest example of transition we have attempted to describe could be shown through the transition from Structuralism (as the pinnacle of Modernist tradition) to Post-structuralism.

*

Let us turn to concrete examples of architectural and urban solutions through which we shall try to justify some of the previously presented theoretical conclusions. The idea of urban planning or urban entities can clearly be traced back to as early as the Ancient Greek cities (though they are not the oldest examples). The Greek idea insisted on a street grid of rectangular crossroads the center of which was taken by the agora. More or less consistently Rome also followed this pattern, creating cities with two main and largest streets, the busiest city arteries which led from north to south, and from west to east. The fundamental rule of medieval cities was to place a cathedral in the center, after which other buildings were built out of plan and in a spontaneous radial position around that center. The Renaissance, as mentioned above, is in a sense the wake of Modernity, therefore an example of such city planning will serve as a comparison.

As an illustration, we shall look at the 15th century urban plan for Milan, called Sforzinda, designed by Antonio di Pietro Averlino-Filarete, a Florentine sculptor and architect. According to the plan, the city is surrounded by walls the layout of which is an eight-point star (inscribed within a circle). Between each two points in the inner angles there is a gate, and each of them was an outlet of radial avenues that each led directly to the center – all the avenues finally converged in a large square, the center of the circle.

Figure 1 – Sforzinda (source)

That the plan should look exactly as it does, has to do with Filarete’s obsession with cosmological symbolism, the application of which in this architectonical solution led to a city reflecting ideal geometric harmony. Naturally, a huge role in such a centralized and circular architectonical layout was also played by the Antique idealization of the circle as a perfect geometric shape, which the Humanists got via Vitruvius’s De architectura libri decem. However, at this point the concerns for our perspective are the modern demands for efficacy and utility which in a Renaissance way merge with Antique ideals⑼.Therefore, all the main avenues which lead from the entrances to the city down to the center passed through a market square located on one radial line equidistant from the center. Most avenues had a canal, for easier cargo export and import. What is most important for Renaissance political views, the center of the city is not occupied by a medieval cathedral but by the ruler’s palace. This may seem like a sort of naïve symbolism but since the manifestation of power in the Renaissance was generally of the physical kind, we cannot underestimate Filarete’s plan – to make control over the community easier for the ruler.

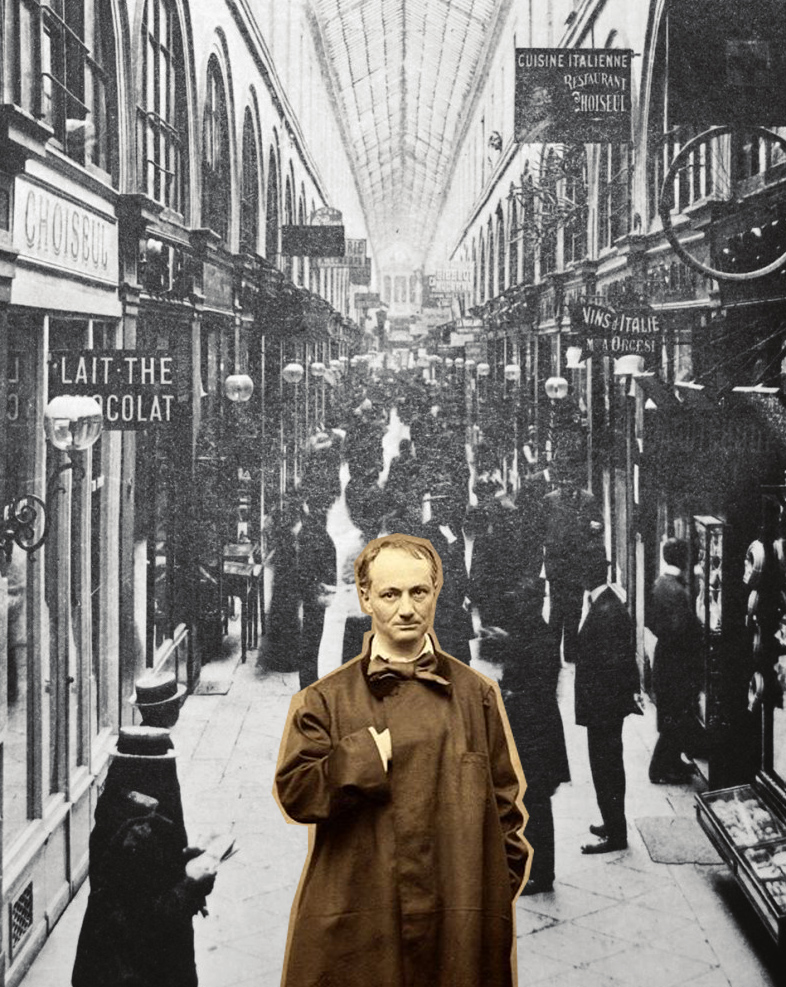

Now, let us look at an example from the late 19th century. Although they are not plans for an entire city, 19th century plans for passages in metropolises imply the design of a certain urban unity. Here, we shall rely on Benjamin’s analysis of those new modernistic urban centers. Thus, a modern matter that connects these two examples is the approach involving thinking and planning. But through Benjamin’s analysis we realize that in the projects of arcade we are not any more concerned just with logistic efficacy, but it is crucial to design the space so that it becomes a dream factory. At the end of the 19th century this means – to enable citizens to imagine themselves as intermediaries to all the charms and sophistication which the new, progressive, capitalist society can clothe them in, which it can feed them with, and by which it can present them with a desired social status. The moment in which a person/consumer looks at their reflection in the shop windows in the arcades, Benjamin symbolically calls phantasmagoria. And in those shop windows there is only the imperative of the perpetuating new, which can best be seen through the phenomenon of fashion, and through which capitalism assumes the character of bourgeois mediocrity, i.e. it sets up a consequential imperative – the worst thing is not being fashionable (Lefebvre: 167).

Figure 2 – Arcade Vitorio Emanuele in Milan (ph. Igor Vukičević)

What are the other differences between these two architectural solutions? There is a ruler in the arcade, too – capital, but he is not physically located in the center (like in Sforzinda). A modernistic ruler is physically absent, but the power of his control is ubiquitous, his laws work. It is a kind of implicit and indirect exercising of rule, in this specific case, through the architectural design of the arcade. Such position of the ruler resembles the leitmotif in the novel Germinal, where the capitalist above all capitalists, together with his capital, is always somewhere inexplicably and unachievably far, somewhere like Paris, which actually exists as a mantra for those oppressed by capital. Thus, it is not only the question of decentralization but of the new mobility and obscurity of the ruling one, whose ideology is hidden in the structure of the dense, ceiled and pleasant architectural plan.

If the plans of a whole city and the arcades seem incomparable, we can take the example of Le Corbusier’s project L’unité d’habitation, by which one building became what once entire residential areas used to be because most every-day needs could be satisfied in it. All that a resident of the building needs is located in it, from a shop, through a recreation facility, up to a resting area. These are all fit together in, as Le Corbusier put it – a functional machine to live in.

Figure 3 – Le Corbusier’s L’unité d’habitation in Marseille (source)

This was a sort of attempt to set up a principle of self-sufficiency of a small community which had already appeared earlier, in Robert Owen’s idea of New Lanark. Surely, this modernistic primate of functionality was born out of the rudimentary modern planning of urban logistics that we saw in Filarete’s work. However, the tendency towards self-sufficiency, i.e. closing the community into one unity, could be related to the capitalist tendency to preserve the achieved class stratification, because such isolated functioning inevitably lessens the share of interaction with the rest of the community. So now we are again in the position from which we can notice the effect of capitalist imperatives on modernistic ideas, their modern predecessor in the form of renaissance late feudal practicality, but also the outlines of the dialectic opposition of atomization – totalitarization, characteristic of Modernism.